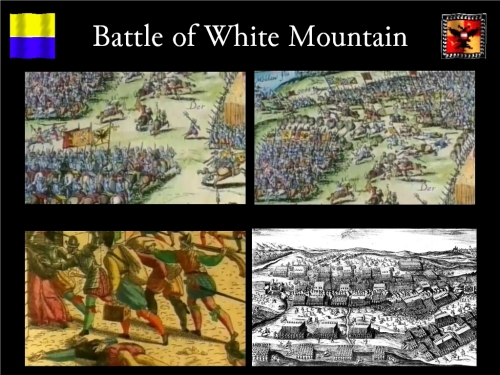

The battle of White Mountain 1620 was fought outside Prague in the Kingdom of Bohemia between forces loyal to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II, and troops of the Catholic League against forces loyal to Frederick V, the King of Bohemia, and Protestant allies, including Hungarians. The battle was a major victory for the Catholics. It was the opening battle in the 30 Years War, a devastating conflict that eventually drew in most of the countries of Europe. The causes for the start of this war, the Bohemian revolt and the battle that ended it are explored below.

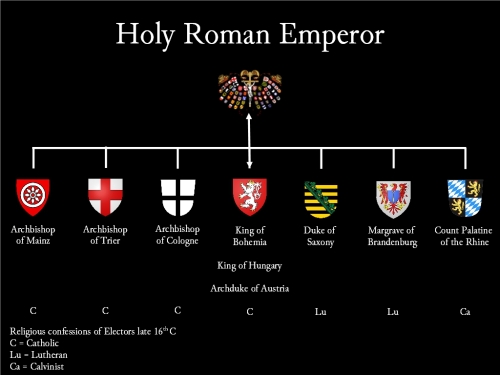

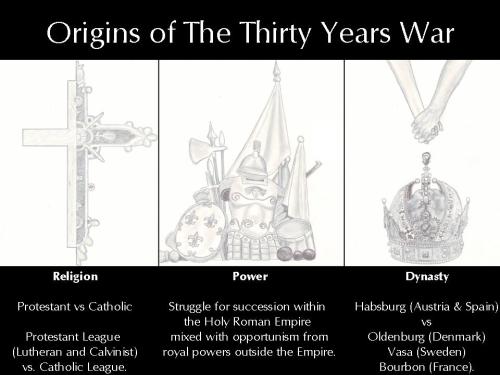

In the sixteenth century, the Habsburg Dynasty ruled much of Europe, and the New World from the Kingdom of Spain, and the Kingdom of Austria, though the office of the Holy Roman Emperor. The Holy Roman Empire in the early seventeenth century was an institution that bound together much of central Europe. It had a Byzantine structure, ruled in name by an Emperor, who was elected by a group of seven electors.

Three of the electors were ecclesiastical, four were secular. In practice, the position was hereditary, with the post going to the chosen Habsburg candidate who was the King of Bohemia, also the King of Hungary and the Archduke of Austria. Given that he was a Catholic, this meant a natural majority of Electors were Catholic.

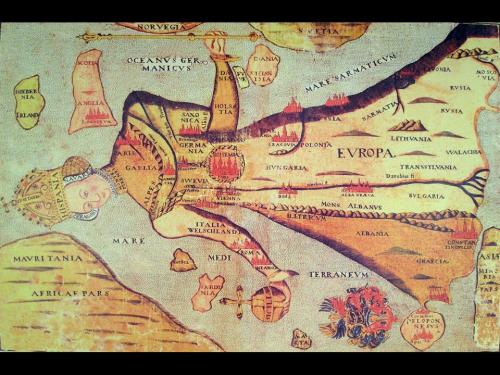

Beneath this structure were three principle groups; the circle of Electors, the circle of Princes and the circle of free cities within the empire. The empire governed itself in a slow manner, designed to reach accommodation and consensus where it could. One kingdom within this structure, Bohemia claimed a special place, due to it’s geographical position and it’s electoral position. The map below (called Europa Regina) purports to show Bohemia at the heart of European affairs

with the head being the kingdom of Spain. Thus the continent, and much of the New World was under the sway of the two great Habsburg powers, related by family. In the age of rule by Dynasty, much depended upon the wisdom of the individual rulers and their councilors.

After the end of the Jagellion dynasty, the crown of Bohemia was made elective by the Estates of the kingdom of Bohemia. In practice the position was seen as hereditary by the chosen Habsburg candidate to become the Holy Roman Emperor from the Austrian branch of the family. Nonetheless, the potential for a dynastic dispute lay within the dilemma of an elected king.

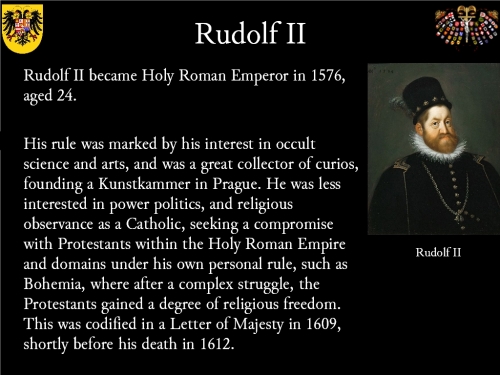

Bohemia under the reign of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (1576-1612)

was at the centre of European affairs. The Emperor based his rule in Prague after 1583 and busied himself in establishing his Kunstkammer, a collection of curios.

Prague, Topographia Germaniae , Matthäus Merian

Prague, Topographia Germaniae , Matthäus Merian

By nature scholarly, melancholic, his marriage bought forth no heirs, which promised future instability.

Across the Holy Roman Empire and its patchwork of nationalities, languages and loyalties lay another fundamental choice; religion.

By the reign of Rudolf II, the Protestant reformation and the Catholic counter reformation had come to a weary acceptance of each other. This was firstly confirmed in the Peace of Augsburg 1555, which established certain territories within the holy Roman Empire as being Lutheran, with the majority remaining Catholic, under the principle (Cuius regio, eius religio) that the Prince of a territory chose the religion and all within had to conform, or leave. At the time of this peace treaty, Lutheranism was the only major choice to become a Protestant within the empire.

However Bohemia had a diverse religious settlement stemming from the end of the Hussite revolution in 1436. A separate branch of Catholicism, the Ultraquists were the heirs to this movement, and lived side by side to the Catholics.

The Fraternity of the Brethren also emerged from the Hussite revolution. They had become reconciled to the Lutheran confession of Ausburg. The Lutherans were the largest section of the Bohemian community. Finally, the Calvinists were the latest Protestant confession to emerge towards the middle and end of the sixteenth century. The Calvinists had an undue representation among the nobility, with only 3% of the population being Calvinist. 15% of the Bohemians were Catholic; the rest one of the Protestant confessions. Thus the kingdom of Bohemia had five churches. It had been originally excluded from the peace of Ausburg, since it was under the personal rule of the Holy Roman Emperor.

Rudolf II and his ruling Habsburg family began a slow process of Catholic renewal, in an attempt to rebuild their faith within the lands they controlled. The most successful of these lay with the cousin of the Emperor, Archduke Ferdinand of Styria.

War with the Ottoman Empire began in 1593, lasting until 1606.

During this inconclusive border war which encompassed Hungary Wallachia and Transylvania, a successful revolt by the Calvinist Stephen Bocskai guaranteed religious freedom for Hungary and Transylvania in the peace of Vienna 1606. Thus the Protestants had forestalled Catholic renewal in these lands. In turn, this precipitated a crisis of confidence in the rule of Rudolf II, bringing the question of his succession, and his ability to rule to the forefront.

In 1607, events began to quicken in pace. The Emperor’s younger brother Matthias managed to exploit a Hungarian rebellion and consolidate a power base there, in exchange with concessions to the Hungarian Protestants. He encouraged Bohemia to follow suit, with the aim of restoring stability within the Empire.

In exchange for continued support, the Bohemian protestants extracted concessions from Rudolf II, in the form of a Letter of Majesty, signed in 1609. This granted tolerance for all religions in Bohemia, and acceptance of the various Protestants. Given the majority of the ruling classes in Bohemia were Protestant, the Catholics were now firmly in decline.

In the broader Empire, tensions between the two religious confessions rose, with the formation of a Protestant Evangelical Union, formed in 1608 around the Palatine with other regions, including Württenburg and Brandenburg. In response, the Catholic league was formed in 1609, led by Maximillian I, Duke of Bavaria. At this point, both were defensive, and stood for their own interests. Tensions rose between the two camps over the Jülich-Cleves inheritance, but the quarrel did not escalate into a large war.

In 1612, Rudolf II died, and the Holy Roman Empire passed to his younger brother, Matthias .

Matthias had no successor, thus the problem of stable inheritance still existed for the Habsburgs. He reconfirmed the privileges won by the Bohemian Protestants in the Letter of Majesty, 1609. In practical terms, the strongest Austrian Habsburg candidate to succeed Matthias was his cousin, Ferdinand, Archduke of Styria. A secret treaty was made between Ferdinand and the Spanish ambassador to the Imperial court, Oñate, leading to a treaty that bore his name. Spain would support Ferdinand’s claim, in exchange for Alsace and the Tyrol, so allowing the movement of Spanish troops on the ‘Spanish Road’. This allowed rapid movements of troops from the Italian territories under Spanish control to the north, into the Spanish Netherlands (Belgium).

Ferdinand of Styria was raised by Jesuits and was a staunch Catholic. Personally devout, he made no secret of his wish that he would rather rule over a desert than over a land full of heretics, and forcefully began the process of re-Catholicisation in his own lands in the late 1590’s. He managed by force to reconvert this territory, earning the sobriquet Ketzen-hammer (hammer of heretics) in the town of Brenner. He was as much guided by faith as reason in this risky policy, which paid off for him.

Despite the Oñate Treay, the path to the Imperial throne for Ferdinand wasn’t guaranteed, for he needed to become king of Bohemia and become an Elector of the Holy Roman Empire this crown gave him. The electoral nature of the King of Bohemia was disputed, with the Habsburgs assuming this was a mere formality, but the nobles of the Bohemian estates wishing to exert their authority.

An illness befell Matthias in 1617, impelling the necessity for the election. The Grand Chancellor of Bohemia, Lobkowicz, summoned the Bohemian Diet in June 1617. Matthias addressed the Diet, calling for the assembly to back Ferdinand’s accession to the crown of Bohemia. The next day a vote was taken. The magnates confirmed Ferdinand in a public vote, with the exception of one, Count von Thurn. One by one the remaining nobles, and knights followed the majority will and confirmed Ferdinand as the King of Bohemia. He was crowned on 19th June 1617, and despite his inner qualms, confirmed the Letter of Majesty.

Emboldened by the apparent ease with which Ferdinand had succeeded, Lobkowicz began a process of re-Catholicization. Firstly, areas of Prague were no longer allowed to administer themselves, but were forced to accept royal magistrates. Then Count von Thurn was forced to accept a less lucrative position within Bohemia. The Protestants found that their literature was subject to censorship by the royal Chancellery, Taken in all, this appeared to be a direct attack on the rights in the Letter of Majesty, confirmed by Ferdinand. Consequently, discontent grew in the ranks of the Protestant nobles.

At the end of 1617, Matthias left Prague for Vienna to aid the election of Ferdinand to the throne of Hungary. taking Lobkowicz with him. Royal power now resided in a circle of regents, who managed Bohemia in the King’s absence. Further infringements on the privileges granted in the Letter of Majesty forced the Protestant magnates to call an assembly in early May 1618 to discuss their grievances. A letter was forwarded to the King, with a view to hearing his reply at another meeting on 21st May. The reply, drafted by Lobkowicz stated that the Protestant assembly had overstepped their authority, and was forbidden to meet again. This was badly received by the members of the Protestant assembly, who suspected that the letter was not genuine, and had been written by the circle of regents in Prague. The meeting on the 21st received another letter, instructing the assembly to dissolve. After a day’s furious debate by the assembly, a meeting of the electors, including Count von Thun

decided that open revolt was the best course of action, and the salvation of their faith would be put to public test.

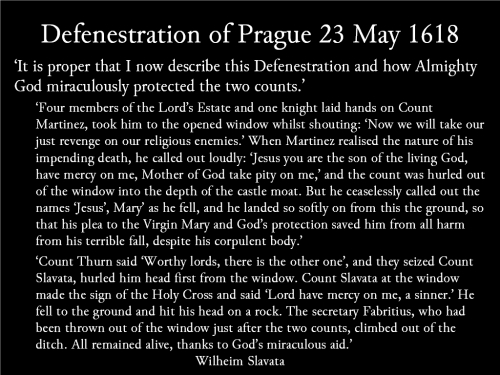

The following day, the 23rd May, saw a group of the Protestant electors marched to the royal castle, the Hradčany, their to confront the royal regents. Lobkowicz, Martinitz, Slavata and their secretary, Fabritius, with a charge of high treason. After heated debate, the accusations settled on Martinitz, Slavata and Fabritius, who were thrown from the window in the defenestration of Prague.

Despite falling some 20m, all three men survived, after falling onto a pile of dung.

Thus the defenestration of Prague made revolt, and an open breach with the King of Bohemia and the Emperor certain.

The war began slowly, with neither side militarily prepared for the ensuing conflict. The Imperialists appealed to the wider empire for help, with Saxony acting to seal its borders with Bohemia, despite being a protestant state. The Evangelical Union was slow to respond to help the Bohemians. Thus despite a religious element to the rebellion, the wider Protestant community were reluctant to join in the fray.

Left to their own resources, small Imperialist (under the command of Bucquoy), and Bohemian (under the command of von Thun) armies began to confront each other in Moravia, between Bohemia and Upper Austria. By September, 1618, the rebel Bohemians had more men in the field, having been reinforced by Count Mansfield and 2,000 Swiss mercenaries, and another 3,000 Silesians. The Imperialists fell back to Budweis, and Krems. The offensive broke down during the winter, with both sides going into quarters.

During March 1619, Emperor Matthias died, and the Bohemian revolt had new implications. No longer were the rebels fighting the King of Bohemia, for Ferdinand was now Emperor elect.

With the die cast, the Bohemians renewed the offensive in April, invading Movaria with 9,000 men, to reach Znaim, the seat of the Moravian Estates. Caught off guard, the Imperialists could do little to stem this attack. Buoyed up by success, von Thun pressed on to try to take Vienna, reaching the outskirts by June 1619. Reinforcements reached Ferdinand, and soon 5,000 men were prepared to defend the city. von Thun’s army was not strong enough to besiege the city, let alone storm it, and he retreated northwards by mid June, lifting the immediate threat to Ferdinand. At the same time the Protestants under Count Mansfield and 3,000 men were caught by 5,000 Imperialist under the command of Bucquoy, and defeated at the battle of Netolitz. Most of the Protestant men were cut down , or captured, with Count Mansfield escaping. The Bohemian advance into lower Austria had failed.

By mid July, the military position for Ferdinand has settle sufficiently for him to call the Imperial Electors together, and he duly became Emperor in August, with a complete majority voting for him, including the Calvinist Palatine.

Now, as Ferdinand II, he could command loyalty across the Holy Roman Empire.

The Bohemians did not seek reconciliation at this point, but sought to distance themselves even more, by reaffirming the Letter of Majesty, and that the Bohemian monarchy was elective, and including the whole of the kingdom (Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and Lusatia) in the process. The elective crown was then offered to Johann Georg, Duke of Saxony, who rejected it, and then to Bethlen Gabor of Hungary. Bethlen was too involved in unrest in Hungary to accept. Finally after election by the Bohemian Estates in August, the crown was offered to the Calvinist Imperial Elector, Frederick V of the Palatinate.

Frederick received a letter from the Bohemians announcing his election, married to Princess Elisabeth, daughter of James I of England, he sought advice from his Father in law. The English Ambassador expressed his belief that “the Count Palatine hath a disposition to accept of that crown.” Frederick V accepted the offer in October, and moved to Prague. In December, his wife gave birth to a son, Prince Rupert.

Ferdinand II had complications of his own. He had inherited a huge debt from Matthias II, which restricted his own military capabilities, having no standing army to count on.

Frederick V, as head of the Evangelical Union, hoped for direct assistance from the princes in the Union. He could also reasonably hope for help from his father in law, King James I. But no help was forthcoming from either quarter, despite pleas from his wife.

Moreover, even the troops he had in the Palatinate would have to defend this territory in any larger conflict that might ensue. Thus external help, in terms of allies with troops or money, could tip the balance in this conflict.

The Bohemian estates, looking to their own resources could field a small army in March 1620. Their hopes lay with Bethlen Gábor, who continued the struggle against the Habsburgs.

Polish mercenary (Lisowczycy) intervention on the side of the Imperialists tied down this second rebellion, with only a limited number of Hungarian troops being available to the Bohemians.

Spain offered troops to Ferdinand II once he became Emperor, but the real advance for the Imperialist cause came with the resurrection of the Catholic League in October 1619, under the direction of Maxillian, Duke of Bavaria. In exchange for territorial concessions in the Palatinate after the expulsion of Frederick V, and all expenses incurred to be paid to Bavaria, a Catholic army was raised, under the field command by Count Tilly. Thus another level of dynastic ambition lay in the quarrel, between cousins Maximilian and Frederick.

The final piece of the military jigsaw came with French led diplomacy in July 1620 between the Evangelical Union and the Catholic League. Neither side wished to start a wider war in Germany, guaranteeing the territorial status quo, but allowing either side to engage in Bohemia. Even the Lutheran Elector of Saxony, Johann Georg, failed to support the Bohemian rebels. He preferred instead to police the borders of Saxony and frustrate Bohemian attempts to gain more support for their army. Thus the quarrel, for now, would be settled in Bohemia, with no hint of the wider conflict that was to come.

Five separate armies began the Imperialist counteroffensive. A small army of 5,000 was left to defend Vienna against Bethlen Gábor, whilst a larger force of 21,000 under Bucquoy moved against Prince Anhalt in Lower Austria. Meanwhile three other armies from the Catholic League pressed the Palatinate. The revolt in Lower Austria collapsed, and Prince Anhalt’s army withdrew to Moravia.

Military discipline was likely to be poor from armies that contained significant numbers of mercenaries, and were subject to infrequent pay. The Catholic League’s army in Lower Austria acted with little discipline, ransacking both Protestants and Catholics alike. Likewise irregular Hungarian cavalry behaved so poorly that Ferdinand was reported to say

‘Indeed, the enemy has behaved so terribly everywhere that one can almost not remember whether such tyranny was ever heard of from the Turks.’

Religious hatred was also part of the fierce response from the troops, as the priests in the Catholic League’s army, led by the Pope’s special representative Father Dominic de Jesus-Maria continued their preaching against the heretics.

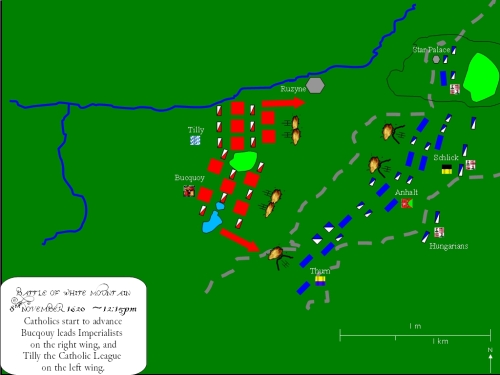

The Imperial – Catholic League army joined near Budweis, and began to move towards Prague by way of Pilsen. The Bohemian force retired back to shadow them. The Imperialists decided to force a battle before the onset of winter, and marched on Prague.

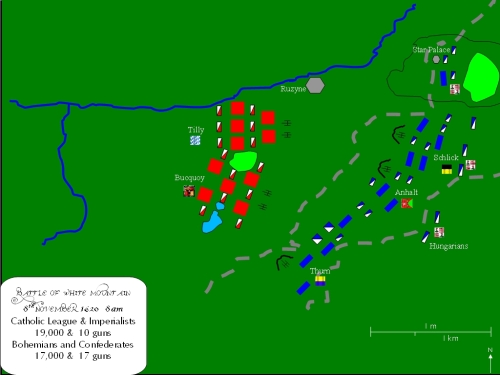

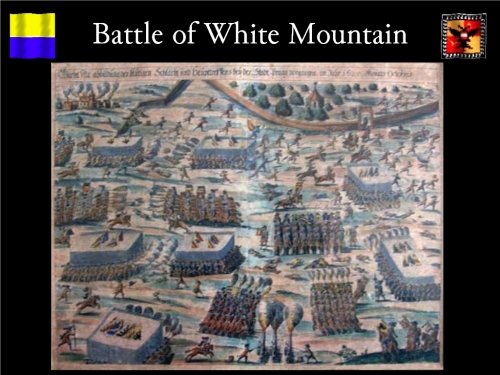

Frederick V joined his army, suffering a mutiny over pay, and lifted morale enough to keep them in the field. They forced marched their army back, overtaking the Imperialists, to reach the White Mountain before Prague on 8th November, 1620.

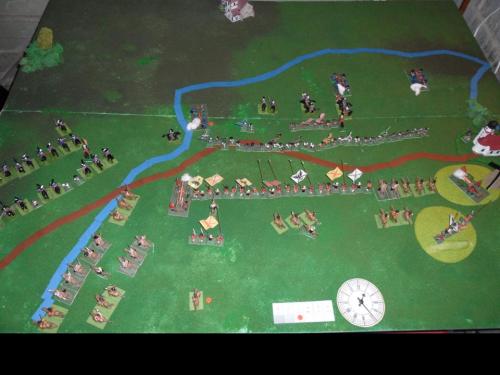

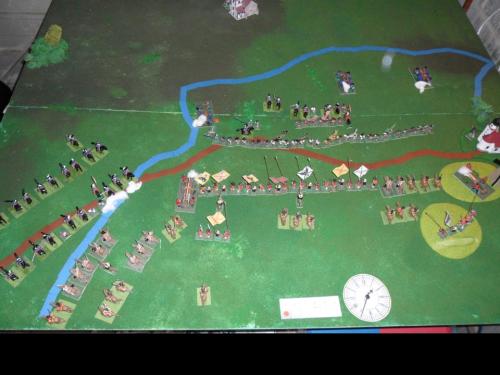

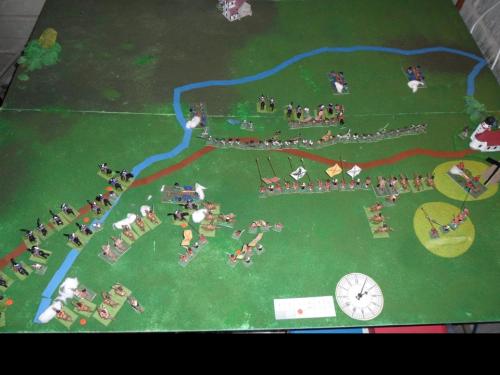

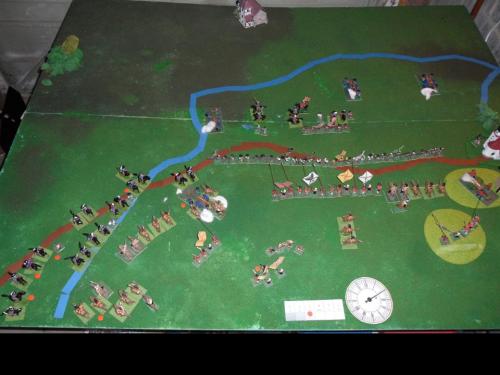

The narrative of the battle was recorded in a letter from the Bohemian commander, Christian of Anhalt to Frederick V.

As it was your Majesty’s order for me to relate the events of the battle of Prague, it is my duty to obey you promptly and to present briefly what I could observe and recognise.

I remember that on Thursday, 5 November, the enemy had started to break camp before ours, which we noticed at 1 or 2 in the afternoon. Your Majesty gathered the main commanders together and asked me what to do. I gave my advice, to wit is that we should head towards Prague as it was our intention, and no doubt also that of the enemy. Upon this, the elder Count Thun interrupted and said he would bet the enemy had no intention of entering Prague as it was completely impossible, and that instead we should come to the aid of the surrounding villages in order to prevent the enemy from conquering them so forcing Prague to surrender. When evening came, however, we clearly understood what the enemy’s intentions were. Then our deliberations shifted how best to prevent the enemy from advancing. We decided that the aforementioned Count Thun, as guardian of the Crown, would march through the night towards Prague with his son’s infantry regiment, and that your Majesty would follow the next morning with the army. Both these decisions were implemented despite the road being long and arduous and not made practicable. We did so well that we arrived at the place two leagues from Prague half a day before the enemy; it was a village called Anhost. It was Saturday, 7 November and your Majesty arrived around midday.

I gave orders to secure billets for the army, and you decided to make a short trip to Prague. Just after you departed, the enemy started to appear and skirmish and that we heard that all the enemy armies had rejoined each other and were making their swift way straight towards Prague. They were surprised to see we had arrived before them. Upon this, I immediately sent 500 musketeers to keep the passage open, which, if the enemy had known about, would have made our arrival difficult.

So it was that at 8p.m., I started the whole army on the night march, and at 1a.m. we arrived at the so-called White Mountain in front of the city of Prague. I set up camp to rest until daybreak. The Hungarians were alarmed by the din made by some of the Cossacks who had pursued them part of the way. Some of our own infantry regiments also seen perturbed and I wasn’t used to that, so I talked to them but it filled me with dread.

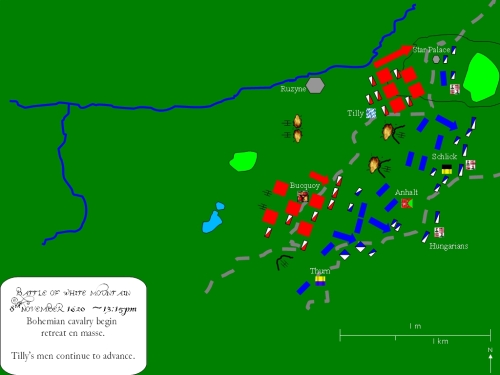

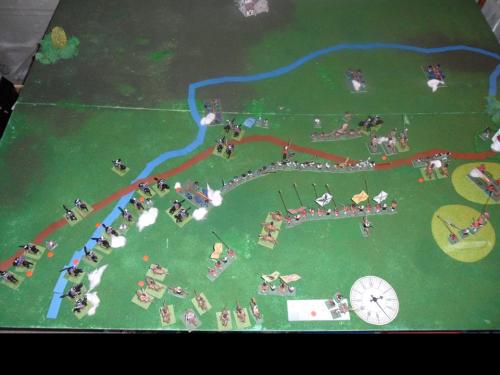

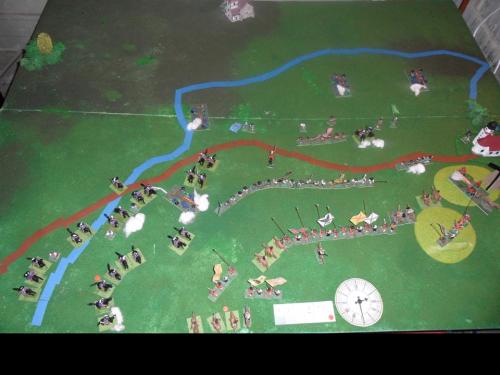

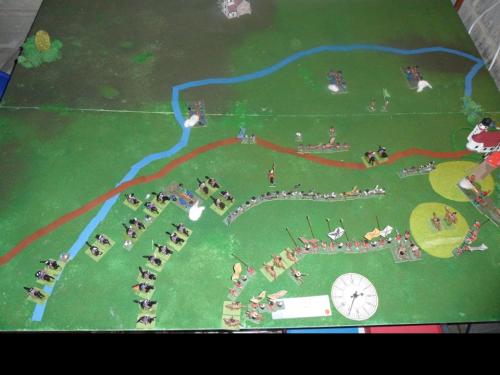

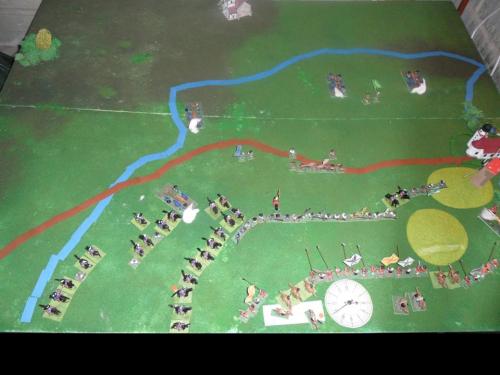

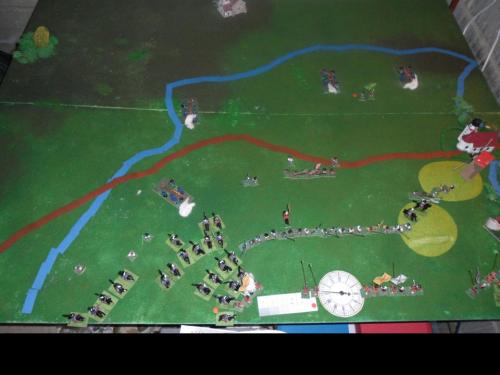

There was fog at dawn on 8 November. When it was gone, we chose the battlefield between the so-called park of the Star Palace and the slope on the other side, so that we had the advantage of the high ground: the park was on the right hand side and the slope on the left, so that the enemy could only attack us from the front.

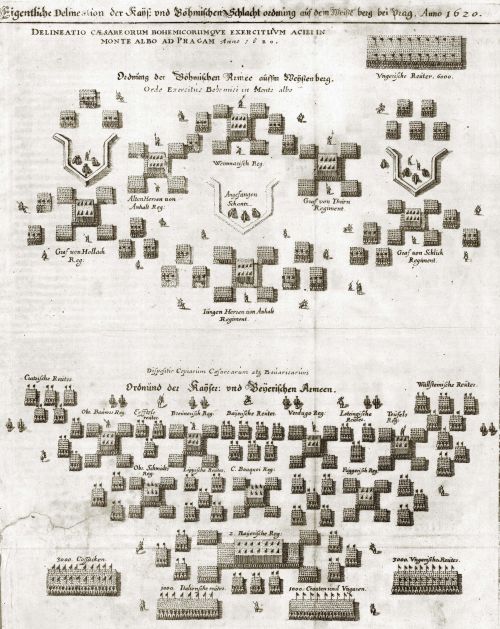

The field having been chosen, the Count Hollach as lieutenant and general chief of staff, ordered the troops to form the order of battle according to the sketch that I enclose .

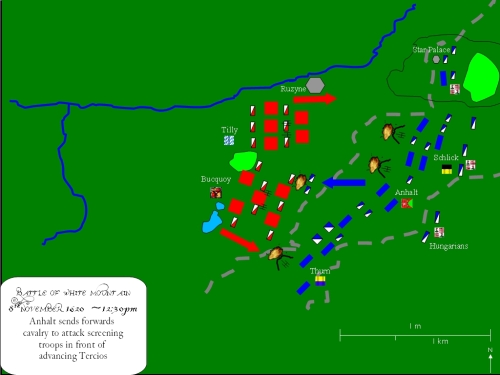

The enemy had noticed, (a bit late) that we had started to move; as soon as they heard us they followed us and the vanguard arrived at around 9a.m. I had called Count Thun to ask his advice as he knew this place very well. He confirmed that it was the best place, and called his son’s regiment back from Prague. Meanwhile, Count Hollach had ordered the infantry regiments to guard the park at various points, to wit that of the Count of Weimar, of my son and the company of guards of your Majesty. He ordered the cannon of the Duke of Bavaria to be entrenched, but the spades that I had brought to the camp at my expense had been damaged so much at Rackonitz, that we only had 400 usable ones left. This meant we can to fetch some from Prague, but it took so long that our entrenchment was hindered and remained far from perfect. The Count Thun decided that the two cannon would be taken to the left flank which damaged the enemy greatly but said pieces were positioned too far away. The Hungarians, that is Colonel Cornis and 300 men, were posted on the right flank. The remaining Hungarians stayed at rearguard, because they wanted to be away from the cannon. They were under orders to advance through the gaps when the battle started and to strike the enemy in the flank. I ordered particularly that 1500 Hungarians had to remain on the left flank, as marked on the plan and I dispatched this order three times to the commander.

The Count Hollach had ordered them similarly and the Count Thun took the above named Colonel Cornis to the very place and showed him personally how they were outside the range to cannon and with which advantage they could do a signal service, but nobody came there. The enemy came through a village of the foot of the mountain where the path was bad but wide enough to allow the passage of formed troops on the right flank. But they would have been seen by us, which they wanted to avoid. So, they moved as I described before.

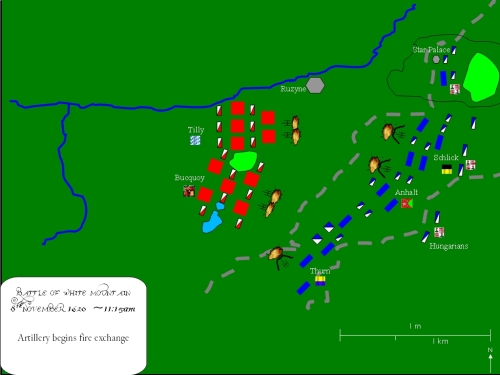

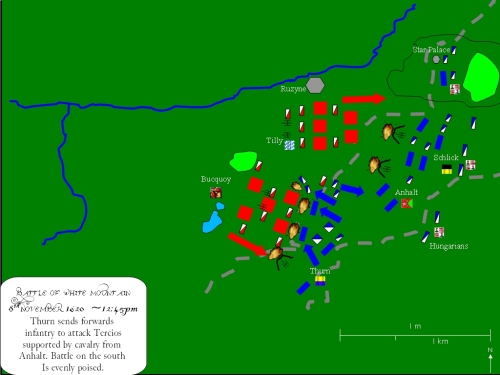

The enemy formed the order of battle at the foot of (and partially behind) the mountain, practically the same forms as us, as they mixed infantry and cavalry regiment left very little space on the front. We could see most ground where our cannon were positioned on the left flank. We damaged them so much that they were obliged to their front back towards their left hand flank.

When I saw them moving, I thought they were going to try something more and, finding the Count Hollach of the same opinion, I immediately informed the troops by the two adjutants to the chief of staff and other first officers.

In the end I saw that the enemy’s vanguard was safely climbing the aforementioned mountain. I was near the two cannon on the left flank, and from there I galloped at the head of Count Hollach’s cavalry where my war horses were, and in no time I could see a large troop of cavalry accompanied by two infantry battalions coming straight at us. This gave me hope as the enemy coming so fast had to have lost order and was going to find us standing firm, in good order, our chiefs in agreement and ready to fight them. Our cannon were flanking their army, we had already dislodged theirs and, although they outnumbered us, they couldn’t see this because of the narrowness of the passage. Moreover, I was well aware that the Count Bucquoy, who was experienced and wise captain, would never advise to start a battle under such circumstances. This made me quite sure I was able to hope for certain victory.

But God, who in his divine wisdom weighs human events, demonstrated his anger at our lack of piety and the offences of which we are all guilty. It must be God who withdrew bravery from our soldier’s hearts, because otherwise it was impossible to believe that such a sudden effeminate terror would sieze so many men as I had seen performing duties so well before. As soon as the enemy arrived at about 300 or 400 paces from Count Thun’s infantry, our soldiers started to shoot without order or sense and, even against expressed orders, shot in the air and immediately started to flee, seemingly in the grip of fear. I then told my cousin Count Solms, your court chamberlain (who was that day honouring me with his presence) that although this didn’t begin auspiciously, I was still hoping for a positive outcome.

At the same moment, and being only just armed, I saw before me my cavalry, which had been levied by Lieutenant Colonel Streiff, with some caracolling and others galloping away. So, I ran towards them and stopped them with my sword to make them returned to the charge. The captains obeyed me, but most of them didn’t really persevere.

Count Hollach arranged his troops so that the ones on the left flank should charge and he told them what to do. The troops of counts Solms and Bubna were engaged with the enemy but with little strength or resistance, so that I could see everything of the vanguard on my left, including the three companies of the estates of Bohemia and the one coming after. Everyone was fleeing, some with the infantry which was running the fastest. My son charged with his cavalry, fought and pushed the enemy back to where they had their cannon.

There, he was wounded twice, as was his brave lieutenant-colonel. My son was then taken prisoner. Count Styrum with Mansfield’s troops charged on the enemy’s musketeers on the side of the park and afterwards he attacked the cavalry. He did his duty with bravery and gained a good reputation. Colonel Stubenvoll also led two or three good charges.

I led the Austrian cavalry charge and they did well. Lieutenant-Colonel Baron Hofkirchen stayed put. But the latter also performed the bad caracole. It was then that I also ordered the major of the Silesians to attack as well, which did well with the aid of his troops, but the resistance was too great. The enemy, however, was stopped and pushed back, so that some of their troops galloped away to regroup.

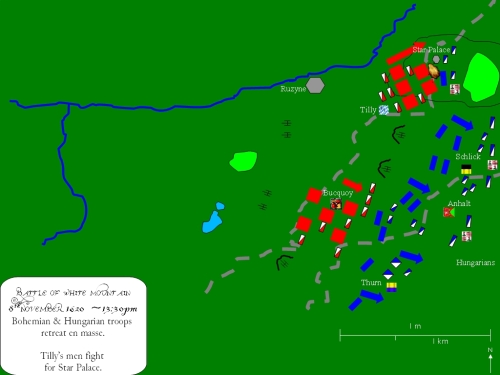

Two enemy infantry battalions fired a great salvo which killed the horse of my chamberlain. One of my gentlemen, Keydel, was also wounded at my side. Those two battalions decided to withdraw too. Our artillery did well and greatly damaged the enemy, which left them perplexed. The regiment of Moravia commanded by Colonel Schlick, as well as the five infantry companies of Lieutenant-Colonel Pechmann showed bravery and remained until the last. As I could see no cavalry coming to our help, and as I had only 16 horsemen near me, and as the enemy was returning with many troops (both cavalry in infantry) I didn’t dare to remain, but withdraw towards the main road that goes towards Prague. I went slowly, hoping that I would find some of our troops waiting, but this was in vain.

When the elder Duke of Weimar went to stop the Hungarians, he found Colonel Cornis accompanied by the very few of his Carey is asked to stand firm he answered ‘the Germans are fleeing’; the Duke and answered ‘they are Germans in the evening, but by morning there will be the same as the Hungarians’; but Cornis although he had turned a little did not want to understand the Latin phrase. Then, the aforesaid Duke came upon another officer who was fleeing and shouted to him that if he didn’t turn back he would shoot him through the head. When he turned, the Duke realised it was one of the colonels who didn’t stop his flight continued fleeing the enemy.

So, I can confirm that when I withdrew, of all our Hungarians, only a hundred were left of the ten thousand, such was the diligence they showed. It was now impossible to stop the troops.

I reached the New Gate where I found Your Majesty together with the routing infantry who had fled before and had already climbed the ramparts. I could only recover six of them who agreed to defend the city walls. The fear was overwhelming in all ran through the Little Side (i.e. the western part of Prague) towards the Old and New Town. Some of them were swimming, especially the Hungarians, some of whom were drowned.

Some of our worst mistakes was that most of our cavalry would not engage properly. The proper way, which I often explained to them, was to reject the bad habit of caracolling when facing the enemy. Those who listened my advice, although defeated, covered themselves in glory, the others in blame. I want to stress this point strongly here, so that this custom of charging without properly engaging is avoided like the plague.

Your Majesty will understand from this account the real reasons for our defeat, and will also understand the defeat was caused not by the enemy’s valour, but by their good fortune and the divine help they received. Surely, God wanted to punish us for our sins, mostly because of the awful treatment and bad pay bestowed upon our soldiers; seeing that the estates of Bohemia wanted their ruin and disbandment, those soldiers were reduced extreme despair and bad behaviour, such that no chief or officer could order them to fight anymore. For me to start of proper explanation of those of those matters, the aforesaid imperfections (and why I wanted to separate from the aforesaid estates and provinces), I would need reams of paper to do them justice. Your Majesty knew about this, even if you couldn’t remedy the matter in any way possible to you. However, for this generation of people, all was in vain as the unhappy outcome proved.

Since the Hungarians were useless that day, and 1,800 killed in the game parks, though no more than 500 cavalry and around 8000 infantry along with six large guns at the battle. If only our men held their grounds, we would have been strong enough with God’s help, thanks to thanks to the advantages we had.

Christian of Anhalt, Letter to Frederick V, after the Battle of White Mountain.

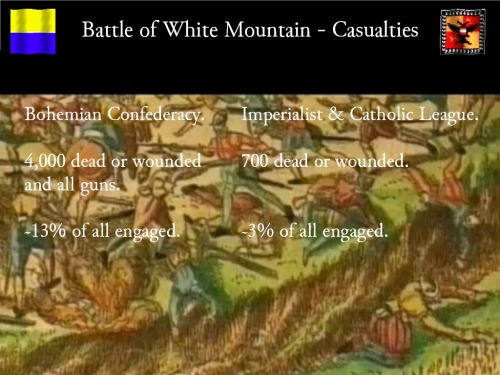

The collapse of the Bohemian army led swiftly to the collapse of the rebellion

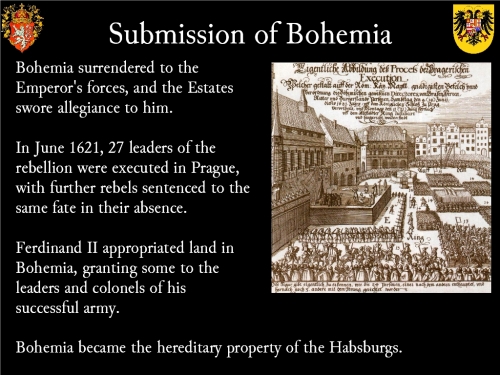

The Bohemian rebels suffered the full weight of Ferdinand II wrath.

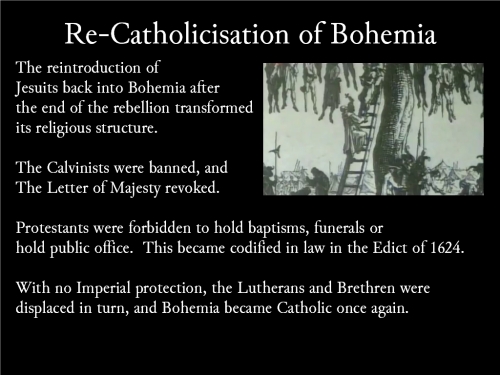

The end of the reign of Frederick V, swiftly led to his banishment within the Holy Roman Empire, and the confiscation of the Palatinate, with the electoral title conferred on Maximillian I, Duke of Bavaria. This act alone ensured the broadening of the conflict into what became the Thirty Year Wars, as re-Catholicisation loomed over Protestant Germany.

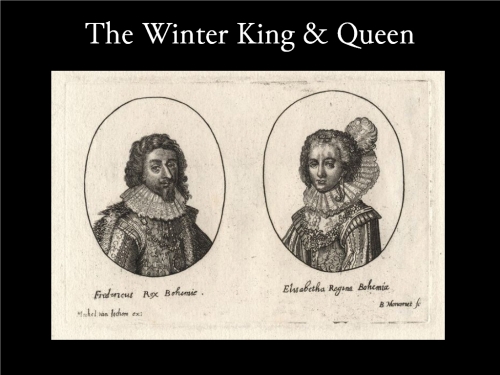

Frederick V was soon to be mocked as the Winter King, due to the brevity of his rule.

A popular song at the time in Germany lamented his fate.

“Oh! Poor winter king, what have you done?

How could you steal the emperor’s crown

By pursuing your rebellion?

Now you do well to flee

Your electoral lands and Bohemia.

You will pay for your mistake with grief

And suffer mockery and shame.

Oh! Pious Emperor Ferdinand, grant him pardon!

Do not hold his folly against him.

He’s a very young man,

Who did not realise beforehand

How much a crown weighs.

Now it is weighing very heavy on his head.

If he had known, he would not have done what he did.”

Yet history would confer on their line great blessings, for their heirs included George I, King of England, who founded the Hanoverian dynasty.