The Battle of Leuthen was fought in Silesia between the Prussian army under the command of Frederick the Great and the Austrian and Imperialist army under the command of Prince Charles of Lorraine. It is a textbook example of how a smaller army may defeat a larger opponent given guile and audacity. The battle formed part of the start of the Seven Years War, the first global conflict of the modern era fought in Europe, America and in the far east.

The story begins in the settlement from the earlier War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) which led to the rise of Prussia.

The Prussians under Frederick the Great had conquered Silesia in the Silesian Wars fought against Austria. The capture of this rich province reduced the Hapsburg Austrian Monarchical lands and made their strategic position harder in maintaining their role as a powerful state in Europe, with territorial interests in the Austrian Netherlands (Belgium), Lombardy and other regions of Italy, complicated further by the exposure to the Ottoman Empire to the south. Clearly Prussia would have to be tackled in a future conflict. Britain had been a strategic ally of Austria since the accession of William of Orange sparked the long duel in Europe with Louis XIV (which would eventually culminate in 1815). Its help to Austria in the recent war was limited, and certainly couldn’t be counted on in a new struggle to regain Silesia from Prussia. The problem to Austria festered like a sore.

Frederick was a noted Francophile and welcomed all things French, including their support in the war. His Uncle George II of England and Elector of Hanover disliked Frederick. The two had minor territorial disputes in parts of Germany between Hanover and Prussia and familial disagreements.

“A bad friend, a bad ally, a bad relation, a bad neighbour, the most ill disposed and dangerous Prince in Europe.”

George II on Frederick the Great

With no love between them, Frederick looked to France to guarantee Prussia against any possible interventions, especially on their exposed borders with Hanover. Likewise, sandwiched between France and Prussia, Hanover and George II looked to Austria and Russia for diplomatic security based on armed forces. France and Britain, were implacable enemies, and faced each other across the globe as colonial rivals.

These amities and enmities set the Quadrille of power which governed the European peace after the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748).

Frederick the Great extended Prussia’s military capabilities in the ensuing peace, but also developed his interests in philosophy and in music, being the very model of an enlightenment ruler, who both made and wrote history. He published his thoughts on politics and warfare (Histoire de mon temps, Discours sur la Guerre, Instructions du Roi de Prusse pour ses Généraux among many other works), always using French. He took his fathers main inheritance seriously, ensuring that the army was drilled to perfection; an instrument of state to be used whenever required.

Peace between Britain and France could not last forever. Conflict broke out in 1754 in North America between French and British colonialists in the French and Indian war, which eventually merged into the Seven Years War.

At the outbreak of the second Silesian war between Prussia and Austria, a secret treaty had been signed between Prussia and France in 1744. This was due to expire in ten years time, and acted as a guarantee to Prussia and its antagonisms with Austria. France and Austria had been rivals for centuries due to strategic encirclement between Hapsburg Spain and the Holy Roman Empire, leading to the state expansions of Louis XIV and the series of wars he triggered. Frederick the Great could not believe that this enmity could be overcome.

The Appointment of Count von Kaunitz was to prove the trigger for the diplomatic revolution between Austria and France. Despite the rivalry, Kaunitz planned on a rapprochement which would seal Prussia’s fate.

Perhaps France could be enticed with the Austrian Netherlands, the old battle ground of Louis XIV‘s wars. This would be bound to provoke a response from Britain and the Netherlands, the Maritime powers that stood against Louis XIV.

In addition, Russia could absorb Eastern Prussia. The Empress Elizabeth of Russia had deep personal animosity towards Frederick, given the personal slights he had made to her. Finally, Sweden could be tempted to take Pomerania.

Despite these obvious gains for all parties, France would not yet come to terms with Austria.

Britain looked to Russia in 1755, with a subsidy convention to station Russian troops near the Prussian borders as a means of preventing Frederick the Great from interfering with Hanover. Despite this, Britain felt compelled to court the Prussians directly, which led to the Treaty of Westminster in January 1756, between Britain and Prussia.

Each party guaranteed the neutrality of Germany, thus hopefully securing the borders between Hanover and Prussia.

The effect of this treaty was immediate. France finally responding to overtures from Austria. Russia failed to ratify the agreement with Britain. and with the prize of territorial gains in East Prussian, sought to join any likely coalition against Prussia, even if it meant war with Britain.

Nivernais, the French ambassador sent to Prussia to assess the situation gave the following character assessment of Frederick .

“Impetuous, vain, presumptuous, scornful, restless, but also attentive, kind and easy to get on with. A friend of truth and reason. He prefers great ideas to others – likes glory and reputation but cares not a rap what his people think of him… He knows himself very well but the funny thing is that he is modest about what is good in him and boastful about his shortcomings. Well aware of his faults, but more anxious to conceal them to correct them. Beautiful speaking voice… I think that, both as a matter of principle and character, he is against war. He will never allow himself to be attacked, as much from vanity as from prudence – he will find out what his enemies are planning and attack them suddenly before they are quite ready. Woe to them if they are not strong, and woe to him if a well organised league should force him into a sustained effort of great length.”

Duc de Nivernais, 1756

These prescient words spoke of the future, unknown at the time.

The quadrille of European power play had resulted in a change of partners.

Austria and France now pledged mutual support in the event that either was attacked, with France pledging not to attack the Austrian Netherlands, and Austria to remain neutral in an war between France and Britain.

Events now moved swiftly. The renversement des alliances between France and Austria as envisaged by Kaunitz was formalised in the Treaty of Versailles in May 1756.

But still France could not be persuaded to attack Prussia. War broke out in 1756 between France and Britain, with the capture of Minorca in June. Austria and Russia had planned invading Prussia in 1756, but the diplomacy exceeded the dilatory nature of military preparations, so the attack was postponed until 1757.

Prussia had some 5 million to fight a combined strength of some 100 million between the three main enemies drawn up against him, and would be outnumbered in strategic manpower by 20:1. In a short war, Prussia could prevail; in a long war, only endure. The borders of Saxony, to the south of Prussia, were only a few days march to Berlin. Attacking and conquering Saxony, an independent state would be an act of war, but would buy the Prussians space in a defensive war, together with potential recruits to their army, material and money. Frederick’s maxim ‘Better to anticipate than to be anticipated’ hinted at his intentions.

‘Negotiations without arms are like music without instruments’

Frederick the Great

Final diplomatic overtures with Vienna in August 1756 failed to resolve any issues between Prussia and Austria. Frederick pointed to picture of Maria Theresa in his study and said to the British ambassador ‘That Lady wants war, and she shall soon have it’.

Seizing the initiative, Prussia launched a pre-emptive attack on Saxony on 29 August 1756. This cast Prussia in the role of aggressor and pushed the diplomatic revolution to its final conclusion. A major European war was now certain.

The battle of Lobositz was fought on 1st October 1756 by 35,000 Austrian troops under the command of von Browne. He arranged his army to hold strong defensive ground; hilly ground to secure his right flank, the village of Lobositz in the centre, and the left flank with the bulk of his force behind marshy ground.

The Austrian artillery made a deep effect on the Prussians, who had never experienced such fierce bombardment, as this account recalls.

‘When the cannon at first spoke out, one of the shots carried away half the head of my comrade Krumholtz. He had been standing right next to me, and my face was spattered with earth, and brains and fragments of skull. My musket was plucked from my shoulder and shattered in a thousand pieces, but in spite of everything, I remained unscathed, thanks be to God.’

Musketeer Reiss

The cannonade even took staff members near Frederick. After being urged to seek shelter, he replied ‘I did not come to avoid them’. The battle went initially badly for the Prussians, who were unable to dislodge the Austrians on their right flank, and conducted wasteful cavalry attacks on the Austrian centre against Lobositz. Eventually the Prussian infantry, under Augustus William, Duke of Brunswick-Bevern, broke the Austrian right flank on the hill, and the village of Lobositz fell after further determined combat. The Prussians were victorious, but suffered 10% casualties in the battle, the Austrians 8%.

Chastened by the experience Frederick wrote:

‘We will have to be very careful not to attack them like a pack of Hussars. Nowadays they are up to all sorts of ruses, and, believe me, unless we can bring up a lot of cannon, we will lose a vast number of men before we can gain the upper hand’.

The Austrian army retreated, and the Prussians closed in on the isolated, starving Saxon army, who surrendered on the 15th October 1756.

The soldiers of the Saxon army were enrolled into Prussian service en mass.

Frederick was present in person while they forced the soldiers to swear allegiance to him. The auditors murmured the words of this so called oath of loyalty in front of the men, and those who refused were punished by the Prussian soldiers… The king so far forgot himself as to use his own stick on a young nobleman, an ensign in the regiment of Crousatz, and he told him: ‘You must be totally devoid of ambition and honour, not to wish to enter the Prussian service!’

Lieutenant General Vitzthum

With his army surrendered, the Elector of Saxony and king of Poland Augustus III fled to Warsaw. Frederick‘s Gambit had paid off, describing the opening of the war as‘setting out the pieces in a game of chess’. Later he remarked ‘To read the newspapers you might think that a pack of kings and princes was bent on hunting me down like a stag, and that they were inviting their friends to the chase. As for myself I am absolutely determined not to oblige them in that respect. In fact, I am confident that I am the one to do the hunting.’

The price that Saxony paid was harsh; the country was heavily taxed for the duration of the war, to an extent that even Frederick acknowledged privately was burdensome.

‘I spared that beautiful country as far as possible but now it is utterly devastated. Miserable madmen that we are: with only a moment to live we make that moment as harsh as we can; amusing ourselves with the destruction of the masterpieces of of industry and of time, we leave an odious memory of our ravages and the calamities which they cause’.

Frederick the Great to Algarotti, 1760.

The armies of Europe went into winter quarters, preparing for the trials that 1757 would bring.

The states of Europe at the critical juncture of 1757 are shown in the satirical cartoon below.

Maria Theresa “Now, sir, mind what you are about. I have a notch more than you”

Frederick the Great “I don’t mind your notch, madam, though I design to have a good stroke at you this time, so mind your eye. Stand out of the way monsieur (Louis XV). I design to send this ball to the She-Bear yonder”

Elizabeth of Russia “I am coming to help you, madam. If you are tired, I will bowl for you.”

Francis I “Ah, Boy, there was a time when I could play with the best of them.”

George II “Ay, ay, never mind. I warrant I’ll get some notches. And if I find the odds against, I’ll hedge off. I can’t say I like her bowling. She seems not to tire.”

Augustus III “I can play no more, I have had such a dam’d knock.”

In the background are Turkey and the umpires; the neutral powers of Holland and Spain. The scorers (the King of Sweden and Duke of Brunswick) are seated on the ground, notching the sticks to count the tally.

Mitchell, the British Ambassador, met with Frederick on 4 May 1757, shortly before the battle of Prague. He found Frederick in good spirits.

‘He was very hearty and cheerful, and told me in a day or two the battle of Pharsalia between the Houses of Austria and Brandenberg would be fought’.

Mitchell

Clearly Frederick had in mind some decisive battle that would settle the war between Austria and Prussia.

The Austrians, under the command of Archduke Charles and von Browne had some 60,000 men, placed on the western hills to the city of Prague. Frederick commanders had some 115,000 men at his disposal, after the second main army under Schwerin and Winderfeldt joined forces with his. 30,000 men under Keith marched to the west to cut off any Austrian retreat, and these troops played no part in the battle. having learnt from their experience at Lobositz, the Prussian main army did not assault the Austrians in a frontal attack on mountainous ground, but sought to attack in the flank by marching around the Austrians and approaching by the more gentle slopes of the Tabor Berg.

The Prussians began marching around their enemy at 7am, but were not in position until late morning, giving the Austrians time to move some troops to counter this threat.

At this point in the war, the Prussian infantry assaulted with their muskets shouldered, to intimidate their opponents. The vanguard attacks were swept by Austrian cannon fire, and the leading Prussian regiments lost up to 50% casualties, including Generals Schwerin , who was decapitated by cannister.

Under this heavy fire the initial Prussian assault fell back, then broke; at 10:30 the battle was evenly balanced. von Browne, the Austrian commander facing this assault ordered his men forward, but in the process opened up a gap between his force and the main Austrian army, still facing along the Ziska Berg under the command of Archduke Charles. von Browne lost his leg to a cannon shot and fell mortally wounded, and so leaderless, the Austrian counterattack broke down. The Prussians found the gap between the two wings in the Austrian line, and began to roll up the main Austrian army, causing them to retreat.

‘Now our fine and agreeable day was plunged into gloom. The whole air was darkened by powder smoke, and by the dust thrown up by the thousands of men and horses. It was like the last day of the world’.

Anhalt Musketeer

The Prussian assault pressed on, causing more chaos and casualties in the Austrian army. Archduke Charles became stricken with a paralysis, and leaderless, their army began to fall back into the city of Prague. The Prussians had won the battle.

The Austrian army lost 14,000 men, with some 5,000 of these captured. The Prussians lost 14,300 casualties, about 21% of the initial force.

‘The battle at Prague must be the greatest and bloodiest in history.’

Frederick

‘Hardly any battle up to the present time has been more murderous. We are condemned to the lamentable fate of earning our laurels with the blood of multitudes of brave men, with tears and endless affliction.’

von Donnersmarck

The price of victory had been high. The highly trained Prussian officers and infantry were being bled to death by the rate of casualties in the battles fought so far.

The remaining Austrian force under Archduke Charles was inside the city of Prague. Frederick hoped to repeat the fate of the Saxon army, and force the capitulation of the Austrians by starvation. The heavy siege artillery made its way to Prague and opened up the attack on 29 May.

By 4 June, it was clear that insufficient damage had been done to the city to cause the much sought surrender, despite the damage inflicted. Reports came in of an army of relief under Marshal von Daun, moving into eastern Bohemia. Bevern was given an army of 25,000 men with orders to push von Daun‘s men away from Prague.

On 13 June, Frederick marched with more troops towards Bevern and his men. By the 16 June, the Prussian strength had risen to some 33,000 men. Close by were the Austrians, with 53,000 men, although this number of troops were not known by the Prussians. On 18 June, the Austrians took position along a series of hills above the Kasier Strasse, the main road in central Europe. von Daun‘s army deployed along the Przerovsky and Krzeczhorz hills. Despite being outnumbered, Frederick would attempt the flanking maneuver of Prague, some six weeks earlier, and wheel the army around to attack the Austrians on the Krzeczhorz hills. These movements were seen by von Daun, who moved part of his reserve to meet the attack.

Major General Hülsen led the Prussian assault, which started to engage at 2pm. Initially successful, Hülsen’s men ran into the Austrian division of Wird, sent by von Daun.

Instead of waiting for more progress from Hülsen’s attack, Frederick ordered the troops of Prince Moritz to attack the main ridge, deviating from the initial plan.

‘For the third time Frederick called out: ‘Prince Moritz, form into line!’ The prince repeated: ‘Forwards, forwards!’ At this the king galloped up and halted with the muzzle of his horse against the Prince’s saddle: ‘For God’s sake’, he shouted, ‘form front when I tell you to do so!’ The Prince at last gave the appropriate order in a sorrowful tone of voice, and he commented… ‘now the battle is lost!’

Duncker

Frederick’s change of mind may have been prompted by him detecting the movement of Austrians towards their right flank, thus denuding their centre. But von Daun‘s men were more plentiful than Frederick knew, and the Prussians advanced into the prepared killing grounds of the Austrian army. Survivors recall hearing the sound of canister balls sounding like hailstones on the bayonets on the infantry, which pointed skywards, as they advanced with shouldered arms.

The Prussian assaults continued throughout the afternoon to no avail. Some progress was made by the cavalry under Major General von Krosigk, south of Krzeczhorz, until the commander fell.

His courage and zeal for the service were undiminished by two bad sword cuts which he received in the head. But a lethal canister shot, which took him in the stomach below the breastplate, at last threw him to the ground… A dragoon saw him fall. He testified that he was still able to call out: ‘Lads, I can do no more. The rest is up to you!’

Pauli

The command was taken up by von Seydlitz.

Frederick rallied unit after unit, imploring them to achieve the seemingly impossible. By Krzeczhorz, one last push by the Prussian cavalry and infantry almost carried the day, until a counter attack by the Austrian de Ligne Dragoons won the day for von Daun‘s men.

The Austrians had finally beaten the Prussians, after losing the previous eight previous battles across two wars. The Austrians had suffered 8,000 casualties, or 15% of their total, whereas the Prussians had 14,000 casualties, or 44%.

Frederick was temporarily stunned by the failure.

The remainder of the Prussian army withdrew, and lifted the siege of Prague on 20 June, falling back into northern Bohemia.

In contrast, on receiving the news of the victory of Kolin, Empress Maria Theresa declared 19 June as the founding day of the Militär Maria-Theresien-Orden, with Marshal von Daun its first recipient.

After the battle of Kolin, Frederick took to writing poetry to console himself.

Pour moi, menacé du naufrage,

Je dois, en affrontant l’orage,

Penser, vivre et mourir en roi.

In the face of the storm,

and the threat of shipwreck,

I must think, live and die like a king.

An even more telling poem he wrote to his sister, Wilhemina, reveals his inner turmoil. The metre is lost in translation from the original in French, but the meaning is plain.

Discord, charmed to see such an America, and feeble mortals crossing the Ocean to exterminate one another, addresses the European Kings: ‘How long will you be slaves to what are called laws? Is it for you to bend under worn-out notions of justice, right? Mars is the one God: Might is Right. A King’s business is to do something famous in this world.’

And thou, loved People, whose happiness is my charge, it is thy lamentable destiny; it is the danger which hangs over thee, that pierces my soul. The pomps of my rank I could resign without regret. But to rescue thee, in this black crisis, I will spend my heart’s blood. Whose IS that blood but thine? With joy will I rally my warriors to avenge thy affront; defy death at the foot of the ramparts, and either conquer, or be buried under thy ruins.

Frederick the Great

But events were no longer his to dictate, and a French army under the command of the Duc d’Estrées put to the field, defeating a combined Anglo-Prussian army under the command of the Duke of Cumberland at the battle of Hastenbach on 26 July. On August 30, the Russian army defeated the Prussians in East Prussia at the battle of Gross-Jägersdorf. Another Franco-Imperialist army began to march towards Thuringia. The Imperialist army contigent, the Reichsexecutionarmee, comprised of men from different states within the Holy Roman Empire in Germany that owed allegiance to Austria.

‘Prudence and audacity may be alternated but not mixed. Having gone to war, it is vain to shrink from facing the hazards inseparable from it.’

Churchill

Frederick needed a decisive victory over the Franco-Imperialist army to regain the strategic initiative. Only audacity would serve this, so on 25 August he divided his army, and took 25,000 men to pursue the approaching Franco-Imperialists, leaving some 41,000 men to face the Austrians in Bohemia. von Seydlitz led the Garde du Corps, having been promoted by Frederick, who recognised in him his coup d’œil, so necessary for cavalry command in this era.

The army marched west, across Saxony, attempting to close with the Franco-Imperialists under the joint command of Soubise and Hildburghausen. The two armies nearly engaged at Gotha on 16 September, but the Franco-Imperialists withdrew when threatened. A raid on Berlin by a small Austrian force caused the Prussians to withdraw back across the river Saale to Torgau. The Franco-Imperialists pursued him, crossing the Saale, and presented Frederick, with his chance of decisive battle. The pursuit began in earnest, and the Reichsexecutionarmee just cleared the Saale at Weissenfels on 30 October.

The Prussians again crossed the river, and by 5 November the long sort combat came to fruition at Rossbach. The Reichsexecutionarmee comprised some 10,900 men; the French some 30,200, a total of 41,100. The Prussians had 21,000 men to oppose them. Again, Frederick would be outnumbered, this time by 2:1. On the morning of the battle, the Franco-Imperialist army formed into 3 columns of march, with the intention of attacking the flank of the Prussian army, still in camp upon the hills above Rossbach.

The move was spotted by midday, and the Prussians swiftly reacted by pulling up their tents and forming into battle order. The Franco-Imperialists saw the Prussian reaction to their move, and took it as a sign that the Prussians were retreating. Instead, taking advantage of the hilly ground, the Prussians were marching to ‘cross the T‘ of the Franco-Imperialist advance.

von Seydlitz, in command of the Prussian cavalry, attacked the advancing Franco-Imperialist cavalry, routing them.

Rather than following them, von Seydlitz reorganized the victorious Prussian cavalry, ready for another attack in the next stage of the battle.

Frederick wheeled the Prussian infantry into a line of battle, forming a shallow ‘V’ at the point of intersection to the advancing Franco-Imperialist columns. The Prussian infantry shattered the front of this attack, and the Franco-Imperialist infantry reeled back in retreat onto their advancing troops, spreading confusion. Soon the entire Franco-Imperialist army was in confusion, and at this moment, von Seydlitz led the Prussian cavalry in for another devastating flank attack.

The Franco-Imperialists ran for their lives, and the battle was won for the Prussians. For the loss of some 550 men, the Prussians had inflicted some 10,000 casualties, the majority captured. Frederick had his desired victory.

Darkness fell about 5pm, and Frederick intended on staying in a nearby castle. It was full of wounded French officers, so the King, an avowed Francophile moved to a house close by, and lodged in the servants quarter.

‘I can now die in peace, because the reputation and honour of my nation have been saved. We may still be overtaken by misfortune, but we will bever be disgraced.’

Frederick

All Europe recognised the scale of this victory, and the inspirational force behind it.

‘We must not forget that we are dealing with a prince who is at once his own commander in the field, chief minister, logistical organiser, and, when necessary, provost-marshal. These advantages outweigh all our badly executed and badly combined expedients.’

Cardinal Bernis

Having dealt with the threat from the west, the Prussians could turn once again to the Austrians in the east.

The strategic situation deteriorated for the Prussians in Silesia during November. The Austrian army, under the command of Prince Charles and von Daun managed to outmaneuver the outnumbered Prussian army under the Duke of Bevern. At the battle of Breslau on 22 November, the Prussians suffered a heavy defeat, and the remainder of this force retreated.

Frederick had to engage and defeat the numerically superior Austrians before winter set in, and drive their army from Silesia. One more supreme effort would be needed from his men. Normally a strict disciplinarian, Frederick changed his style of leadership before the battle of Leuthen, offering atonement to the remainder of Bevern’s army, in exchange for future good conduct in the forthcoming battle. He circulated freely among his troops to hear their stories and offer his encouragement.

He called his general staff to his tent on the morning of 4 December, to give the Parchwitz address.

The do or die sentiment made the situation plain to all, and the address survived long after the event as a reminder of the nature of the struggle that the Prussians faced.

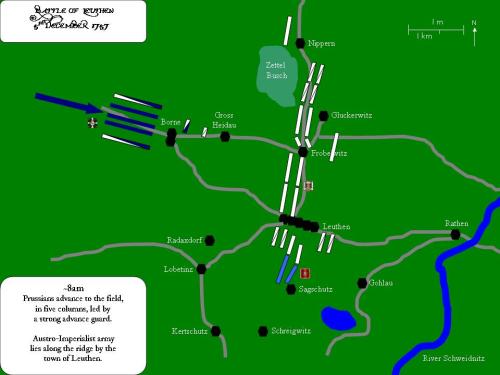

The Prussian army moved forwards to Breslau, with the aim of bringing the Austrians to battle. Prince Charles and von Daun concurred and moved their army towards Leuthen, occupying the ridge across the town. With 66,000 men and 210 guns, the Austrians believed they could defend against attack from the impetuous Prussians. Frederick had only 39,000 men and 170 guns. Once again, he would have to defeat an enemy superior in numbers on chosen ground, suited to defence.

Early on the morning of 5 December, the Prussian army rose, with light snow on the ground.

The troopers were standing by their horses and clapping their hands to keep warm. ‘good morning Gardes du Corps!’ ‘The same to you, Your Majesty!’ replied an old cavalryman. ‘How goes it?’ enquired the king. ‘Well enough, but its bloody cold!’ ‘Have a little patience, lads, today is going to be a little too hot!’

Hildebrandt

The Prussians moved towards the Austrian position, with infantry columns in the centre, flanked by cavalry on each side, and an advance guard ahead, with Frederick.

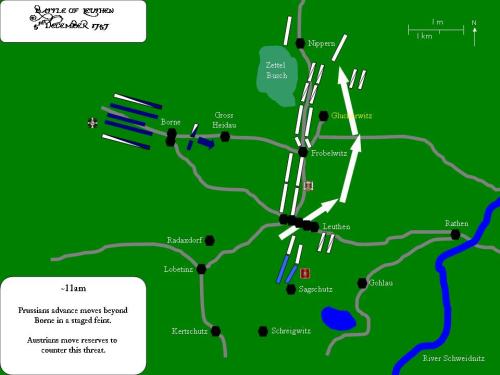

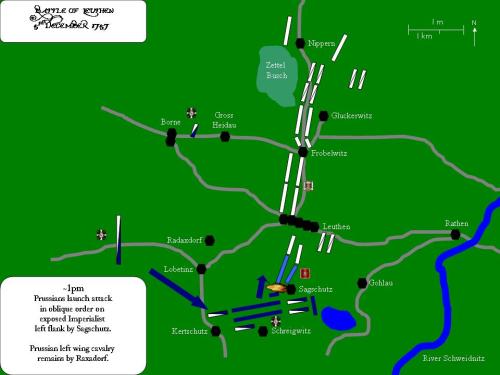

The advance guard drew up before the village of Borne, and the Prussians attacked and scattered or captured the Austrian Hussar outposts. At leisure, Frederick surveyed the Austrian position. His army had emerged about the centre of the Austrian army, deployed along the hills that straddled the town of Leuthen. The Austrian right wing was secure against woods, but their left wing was exposed, with no cover. The Prussians knew this ground intimately, as it was the place the army performed its autumnal pre-war maneuvers. Once again, Frederick would employ a flank attack to compensate for his lack of men. To aid this, the Prussians launched the advance guard beyond the village of Borne, which convinced Prince Charles that the Prussians would attack his centre.

He correspondingly moved reserves to counter this apparent threat. Late in the morning, the Prussian army swung south and marched out of view from the Austrian high command, their movements being shielded by a series of low hills.

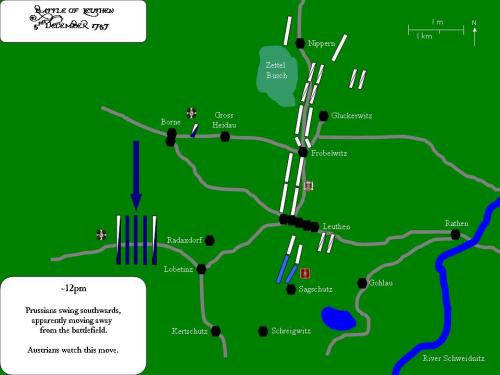

The Prussians had disappeared, apparently retreating before a superior force. The Austrians did not move from their ridge, and were content to let the Prussians go.

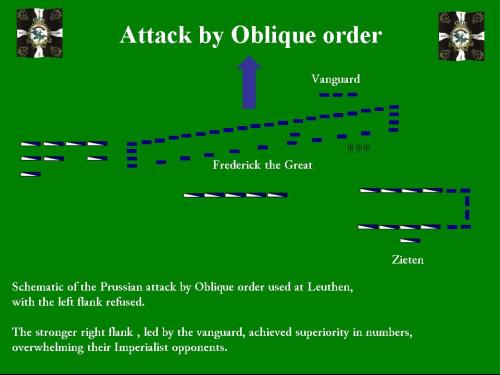

But the Prussians were working their way South, towards the village of Lobetinz, before swinging their way back to the North East. During the later stages of the march, the Prussians managed to convert their columns of march to lines of attack in their formidable oblique order as the army swung around between the villages of Lobetinz and Sagschutz.

The Austro- Imperialist troops were largely unaware of the storm about to break on them. At the extreme left of the Austro- Imperialist left flank were Württemburgers and Bavarians, not the best troops in their army.

Facing them in the vanguard, were elite Prussian units of the 26th (Meyerinck) and 13th (Itzenplitz) infantry regiments. Prior to the attack, Frederick addressed the men, and let them know of the importance of success.

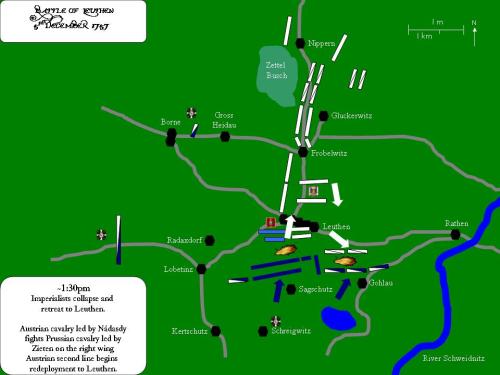

After an initial resistance by the Württemburgers, the Austro- Imperialist infantry retreated.

A cavalry counter attack led by Nádasdy was repulsed by the Prussian cavalry of the right, led by Zieten, with the Prussians victorious. The Austrian cavalry fled, and the Prussian cavalry pursued the easier target of the routing Austro- Imperialist infantry.

The Austrian army faced the collapse of their left wing. Prince Charles ordered the army to take up a new position at right angles to its original line, to face the Prussians square on. The line would run either side of the town of Leuthen, which would become the linchpin of the new position.

The redeployment was slow, with the second Austrian line moving first, then reserves, and finally the troops to the north of the original position. This led to a unsteady delivery of troops to the new front.

The Prussian infantry stormed the town of Leuthen after fierce fighting. The position for the Austrian army was now critical, and a counterattack urgently needed.

The Austrian cavalry of the right flank, under the command of Luchasse was originally deployed to the North. They swept down across the plain towards the left wing of the Prussian army, extended around the Butter Berg, along the new line of battle by Leuthen.

This was intercepted in turn by the Prussian cavalry of the left wing, under the command of Dreisen.

A fierce mêlée broke out, with the Prussian Bayreuth Dragoons, the heroes of the Battle of Hohenfriedberg in 1745 just holding their own, until the second line of Prussian Cuirassiers arrived to scatter the Austrians.

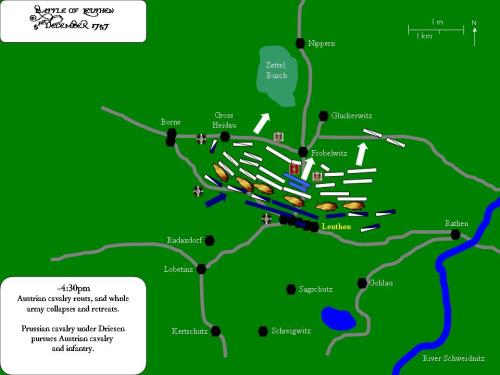

The Prussian cavalry then ploughed into the exposed flank of the Austrian infantry, and their army collapsed, and routed.

Whole units ran for their lives, being pursued by Prussian cavalry and infantry. Only darkness saved the Austrians from a greater disaster from that which befell them, with over 33% of their army casualties by the evening. Frederick ordered a small pursuit force of cavalry and infantry to follow the fleeing Austrians, reaching a bridge across the river Wistritz.

As the snows fell, Frederick entered a nearby castle, to find it full of wounded Austrian officers. ‘Good evening gentlemen; certainly you weren’t expecting me here.’ he said by way of introduction, before making off for another location.

In the darkness, the victorious Prussian army marched and reorganised. A lone Prussian soldier began singing Rinckart’s Lutheran hymn ‘Now we all thank our God’ (based on Sirach:50 v22 – 24), and the song was taken up by the army.

Described by many later, this vivid experience of survival, and thanks in the face of the adversities of the eighteenth century battlefield became the legend of the Leuthen Chorale.

The pursuit proper of the Austrian army began on the 7 December, with the Austrians fleeing towards Bohemia.

‘Just imagine a cloudburst descending from the hills with thunder and lightning, and flooding the valley at the foot. In the same way we saw countless troops flowing under our eyes. Every street became a river of men, and every lane a torrent.’

Belach

By the 21 December, further Austrian troops surrounded in the Schweidnitzer Tor surrendered, a total of 17,000 men. The Austrian army had lost over 66% of their total, and Frederick had won the most famous victory of the age.

The battle has kept the Prussians in the war, although no-one knew at that time the conflict would continue until 1763.

With joy will I rally my warriors to avenge thy affront; defy death at the foot of the ramparts, and either conquer, or be buried under thy ruins.

Frederick the Great