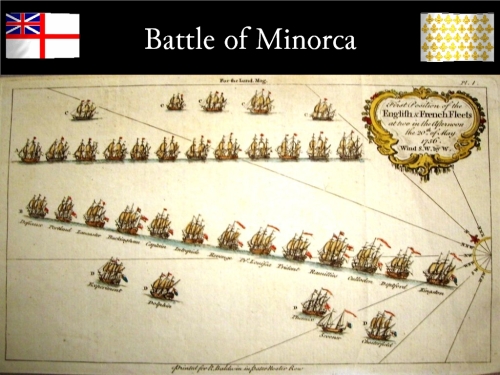

The Battle of Minorca, fought between the English and the French was the first major naval battle of the Seven Years War. Although tactically indecisive, the result led to a major strategic victory for the French, with the capture of the Island of Minorca.

The Island of Minorca was invaded by troops from Great Britain in 1708 during the War of the Spanish Succession, and was acceded to it, together with the island of Gibraltar as part of the negotiations between Spain and Great Britain in the peace of Utrecht.

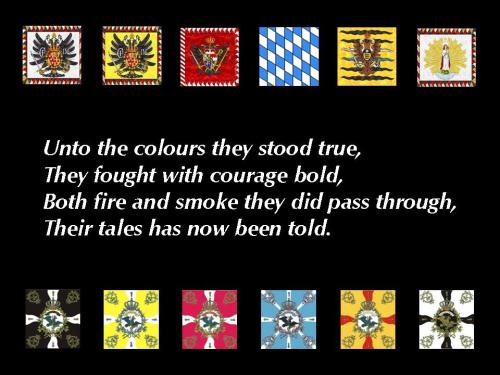

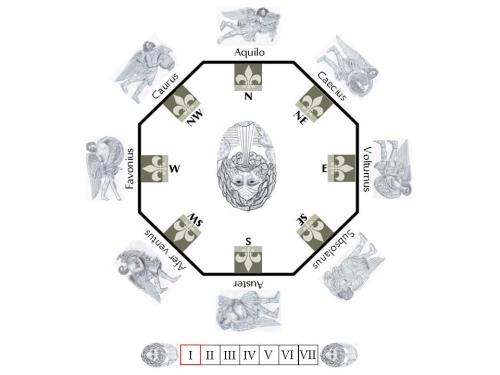

The islands deep natural harbour of Port Mahón offered a naval base for British interests to rival the French port of Toulon, home of their Mediterranean fleet. During the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748), the island remained under British rule. At the end of the war, the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748) left the strategic situation in the Western Mediterranean thus:-

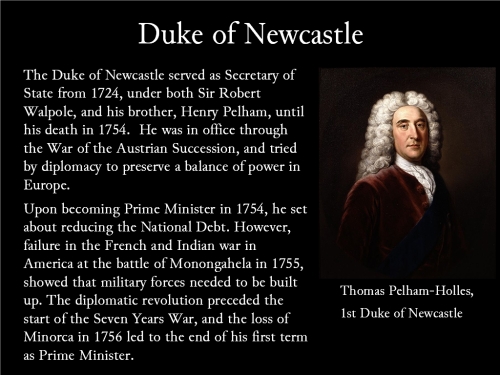

The death of the Prime Minister of Great Britain, Henry Pelham led to the succession of his brother, the Duke of Newcastle. Having long served as Secretary of State, he understood the need to preserve the balance of power in the European state system to prevent a widespread war.

He had hopes of helping reduce Britain’s national debt, but actions in the French and Indian war intervened, resulting in expediture on the military as war beckoned again. The political tensions between France and Great Britain in the War of the Austrian succession were only partially resolved. During the 1750’s, they were unofficially at war in a series of border conflicts in North America, along the Ohio river valley, with the settlers of both nations claiming the vast land between the Appalachian mountains and the Mississippi.

A battle at Fort Necessity in 1754 between The French, and their Indian levies, defeated the British under the command of George Washington.

“I fortunately escaped without any wound, for the right wing, where I stood, was exposed to and received all the enemy’s fire, and it was the part where the man was killed, and the rest wounded. I heard the bullets whistle, and, believe me there is something charming in the sound.”

George Washington, 1754.

The French and Indian War threatened the peace of Europe at a time when peace between France and Great Britain was the declared intent. Despite this, the cold war between their colonists continued, as both sides transferred troops to America. Gathered intelligence led the British to ascertain when a French Atlantic fleet set sail for America.

The Royal Navy, under the command of Vice Admiral Edward Boscawen and 11 ships pursued the French Navy and their troop transports. Most managed to land their men at Louisbourg in Nova Scotia, but three separated from the fleet in fog.

On 8th June 1755, HMS Dunkirk, HMS Defiance and HMS Neptune found the French ships Dauphin Royal, Alcide and Lys.

The French called out to the commander of the Royal Navy vessel “Are we at war, or at peace?” to which the English replied, “At peace, at peace.” After a brief discussion, the Royal Navy ships opened fire on the three French ships.

After a five hour battle, the Alcide and Lys were captured, along with some 2,000 prisoners; troops from the Régiment de la Reine and the Languedoc regiment. News returned to London, causing concern.

‘It gives me much concern that so little has been done, since anything has been done at all… Voilà the war has begun.’

Hardwicke to Anson, 1755.

Worse news was to follow. The arrival of two regiments of foot under the command of Major General Braddock led the British to try to take Fort Duquesue in the disputed Ohio country. His expeditionary force was heavily defeated by a combination of French regulars, Canadien irregulars and Indian levies at the Battle of the Monongahela on 9 July 1755, due to their superior tactics of frontier fighting.

General Braddock’s last words were reported to have been: “We shall know how to fight them next time.”

The resulting French victory ensured the Ohio country remained under their control. These two actions, together with continued aggressions on the American continent, and at sea propelled both nations towards war, which would inevitably involve the European theatre.

Where could France fight the British? In terms of its navy, with both Atlantic and Mediterranean ports, options could include furthering the war in the Americas, and possibly the Caribbean; a direct invasion of Great Britain (the Atlantic options), or an invasion of Minorca (the Mediterranean option). The time of expansion for the French Navy had long passed from its prime under Colbert in the 1680’s, so it was outnumbered by the Royal Navy. Nonetheless, it had undergone a second renaissance under Maurepas in the 1740’s. By concentrating what fleet it had, it could gain local superiority in any action, provided the British were prevented from concentrating their own.

In terms of its army, French troops would be required for all the options above, with a further option for war against Hanover, and the Crown interest of George II, its Elector in the mainland European theatre, provided that Austria would remain neutral, and break its historical alliance with Great Britain.

More so than Britain, the French naval strategy would follow the strategy for their army, due to the constraints of numbers. Conversely, the Royal Navy also faced challenges. Its strength in terms of numbers of ships and men had been run down since the end of the War of the Austrian Succession by the Pelham administration. Nonetheless, on paper it enjoyed at least a superiority over the French Navy in terms of ships. It would need this, given its territorial duties included three distinct regions. Firstly the Atlantic Ocean, with the American and Carribean colonies. Secondly, the Mediterranean Sea, and the bases at Gibraltar and Minorca. Finally control of the Western Approaches, and the English Channel, which were key to safeguarding Great Britain from potential invasion. Together these vast areas of sea could swallow up the available resource.

The following reports received by the Admiralty demonstrate the confused picture emerging of the French threat.

The blow, when struck, could come anywhere according to the intelligence. Sparring between the two nations continued at sea.

War became more certain as the French Crown made its plans.

In response, the Admiralty prepared for either invasion, or a possible assault on Minorca from the French fleet in Toulon. Caution urged that the Royal Navy should protect against invasion.

“I think it would be a dangerous measure, to part with with your Naval strength from this country, which cannot be recalled if wanted, when I am strongly of the opinion that whenever the French intend anything in earnest, their attack will be against this country.”

Anson to Hardwicke, December 1755.

Diplomatic events in early 1756 accelerated the move to war. The Treaty of Westminster between Britain and Prussia was signed in January 1756.

Each party guaranteed the neutrality of Germany, thus hopefully securing the borders between Hanover and Prussia. In response, and unbeknown to Great Britain, a diplomatic revolution (Renversement des Alliances) was underway within Europe. Centuries of animosity between Hapsburg Austria and Bourbon France were being addressed to one of mutual support in times of war, with the lead coming from the Austrian State Chancellor, Count von Kaunitz. Such a system would lead to France being free to attack British interests globally wherever suited, whilst leaving Austria to settle its score with Prussia. The first treaty of Versailles between Austria and France was signed on 1st May 1757. Before then, France would strike a blow at Britain.

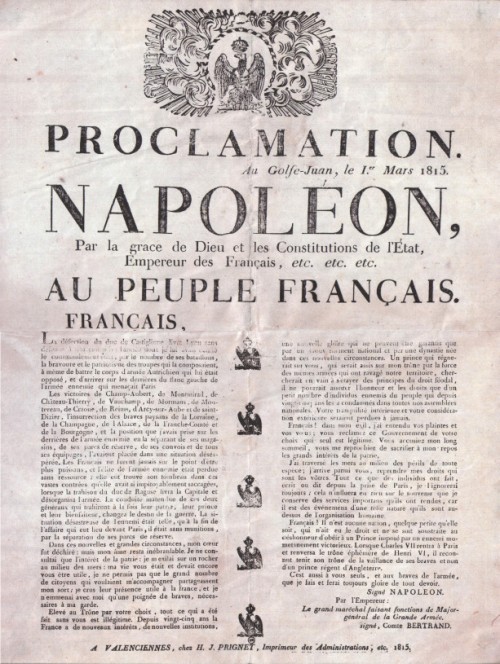

With these diplomatic moves in motion, the French fleet made ready for an invasion of Minorca, with the decision being made on 15 March 1756.

At this point, the French plan was unknown to the British, who in turn had decided to sail a small squadron of ten ships to the Mediterranean, under the command of Vice Admiral, the Hon. John Byng.

Having served in the Mediterranean during the War of the Austrian Succession, he knew the sea and its conditions. His father, George Byng, viscount Torrington, had also fought with success against the Spanish in the Mediterranean in 1718. Given his experience and connections, Byng was formally appointed commander of the Mediterranean fleet on March 11, 1756.

Anson had his reservations regarding Byng, considering him weak on leadership and initiative.

“I don’t know how it comes to pass that unless our commanders-in-chief have a very great superiority of the enemy, they never think themselves safe”

“Byng’s squadron could beat anything the French had”

Anson, 1756.

Nonetheless, he was promoted from Vice-Admiral to Admiral of the Blue on March 17, 1756. Upon reaching his command, and making his flagship HMS Ramilles, he found his fleet short of men, and a few ships decrepit. He was not permitted to take sailors from other ships, and his orders received on April 1, 1756 indicated that soldiers were to be taken instead of the normal complement of Marines. Byng’s orders from the Admiralty had three instructions; to watch for any French fleet which would pass by Gibraltar, and detatch as many ships required from his own fleet to shadow them (if necessarily all the way to the Americas, their suspected target), secondly to ascertain the state of affairs in Minorca and to relieve any siege taking palce, and finally if neither of these events had occurred to move to Toulon and commence a blockade of the French fleet. Byng sailed on 6 April, 1756, reaching Gibraltar on 2 May 1756.

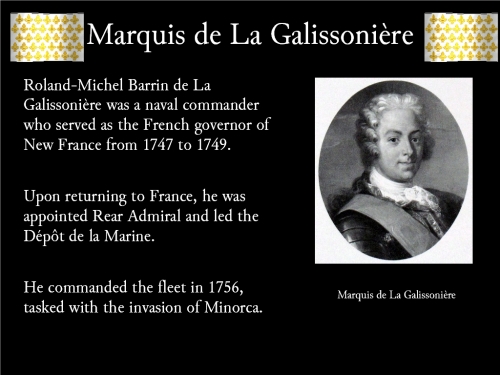

Unbeknownst to Byng, the French had set sail from Toulon on 10 April, with an invasion fleet of 12 ships of the line, escorting 176 transports and 12,000 men. The fleet was commanded by the Marquis de La Galissonière, a commander unproven in combat, with the invasion troops led by the duc de Richelieu.

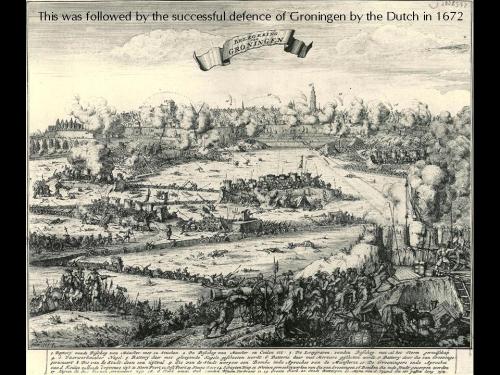

Arriving on 18 April, the French immediately invaded Minorca, and succeeded in taking all the island, except St Philip’s Castle, which was held by the British under the command of General Sir William Blakeney. St Philip’s Castle guarded the entrance to Port Mahón, and thus a siege began.

Admiral Byng and the governor of Gibraltar, Lt. General Folke, received news of the invasion of Minorca and the siege of the remaining British troops on the island. Despite orders to supply troops to Byng, Folke kept his troops on Gibraltar, and offered little assistance, in the hope to keep the island ready for an expected invasion. Both Byng and Folke wrote to the Admiralty offering their explanation for the impasse between the two commanders. Byng’s letters were poorly received by the Admiralty, where his downbeat tone regarding his difficulties and chances gave the impression of a man not willing to fight.

Byng was reinforced by Captain Edgecombe and the small Mediterranean squadron, and the combined fleet set sail for Minorca on 8 May. It comprised of 13 ships of the line, and 4 frigates.

By 19 May, Byng’s squadron arrived off the coast of Minorca, to the consternation of the French troops besieging St. Philip’s Castle. The duc de Richelieu, commanding the French remarked.

“Gentlemen, there is a very interesting game being played out there. If Monsieur de La Galissonière defeats the enemy, we may continue our siege in carpet slippers. But if he is beaten, we shall have to storm the place at once, at any cost.”

duc de Richelieu, 1756.

Attempts to communicate between the besieged British force and the relief squadron failed when the French fleet led by the Marquis de la Galissonniere, was sighted and Admiral Byng gave the signal to his squadron to chase the enemy. The wind became light and the two fleets did not engage until the following morning.

The following account of the battle was given by Admiral Byng on May 25, several days after the battle had concluded. It was addressed to the Admiralty Board.

SIR, I have the pleasure to desire that you will acquaint their Lordships that, having sailed from Gibraltar the 8th, I got off Mahon the 19th, having been joined by his Majesty’s ship Phoenix off Majorca two days before, by whom I had confirmed the intelligence I had received at Gibraltar, of the strength of the French fleet, and of their being off Mahon. His Majesty’s colours were still flying at the castle of St. Philip; and I could perceive several bomb-batteries playing on it from different parts. French colours I saw flying on the west part of St. Philip. I dispatched the Phoenix, Chesterfield, and Dolphin ahead, to reconnoitre the harbour’s mouth; and Captain Hervey to endeavour to land a letter for General Blakeney, to let him know the fleet was here to his assistance; though every one was of the opinion we could be of no use to him; as, by all accounts, no place was secured for covering a landing, could we have spared the people.

The Phoenix was also to make the private signal between Captain Hervey and Captain Scrope, as this latter would undoubtedly come off, if it were practicable, having kept the Dolphin’s barge with him: but the enemy’s fleet appearing to the south-east, and the wind at the same time coming strong off the land, obliged me to call these ships in, before they could get quite so near the entrance of the harbour as to make sure what batteries or guns might be placed to prevent our having any communication with the castle.

Falling little wind, it was five before I could form my line, or distinguish any of the enemy’s motions; and could not judge at all of their force, more than by numbers, which were seventeen, and thirteen appeared large. They at first stood towards us in regular line; and tacked about seven; which I judged was to endeavour to gain the wind of us in the night; so that, being late, I tacked in order to keep the weather-gage of them, as well as to make sure of the land wind in the morning [20 May], being very hazy, and not above five leagues from Cape Mola. We tacked off towards the enemy at eleven; and at daylight had no sight of them. But two tartars, with the French private signal, being close in with the rear of our fleet, I sent the PRINCESS LOUISA to chase one, and made signal for the Rear-Admiral, who was nearest the other, to send ships to chase her. The PRINCESS LOUISA, DEFIANCE, and CAPTAIN, became at a great distance; but the DEFIANCE took hers, which had two captains, two lieutenants, and one hundred and two private soldiers, who were sent out the day before with six hundred men on board tartars, to reinforce the French fleet on our appearing off that place. The PHOENIX, on Captain Hervey’s offer, prepared to serve as a fire-ship, but without damaging her as a frigate; till the signal was made to prime, when she was then to scuttle her decks, everything else prepared, as the time and place allowed of.

The enemy now began to appear from the mast-head.

I called in the cruisers; and, when they had joined me, I tacked towards the enemy, and formed the line ahead. I found the French; were preparing theirs to leeward, having unsuccessfully endeavoured to weather me. They were twelve large ships of the line, and five frigates.

As soon as I judged the rear of our fleet the length of their van, we tacked altogether, and immediately made the signal for the ships that led to lead large, and for the DEPTFORD to quit the line, that ours might become equal to theirs.

At two I made the signal to engage: I found it was the surest method of ordering every ship to close down on the one that fell to their lot. And here I must express my great satisfaction at the very gallant manner in which the Rear-Admiral set the van the example, by instantly bearing down on the ships he was to engage, with his second, and who occasioned one of the French ships to begin the engagement, which they did by raking ours as they went down.

[When the signal to engage was made, the van under rear-admiral Temple West kept away in obedience to it, and sailed towards the French, thus reducing their cannon fire. They received three raking broadsides from the French, and were seriously dismantled aloft. The sixth British ship (Intrepid) counting from the van, had her fore-topmast shot away, flew up into the wind, and came aback, stopping and doubling up the rear of the line.]

The INTREPID, unfortunately, in the very beginning, had her foretopmast shot away; and as that hung on her foretopsail, and backed it, he had no command of his ship, his fore-tack and all his braces being cut at the same time; so that he drove on the next ship to him, and obliged that and the ships ahead of me to throw all back. This obliged me to do also for some minutes, to avoid their falling on board me though not before we had drove our adversary out of the line, who put before the wind, and had several shots fired at him by his own admiral. This not only caused the enemy’s centre to be unattached, but the Rear-Admiral’s division rather uncovered for some little time. I sent and called to the ships ahead of me to make sail, and go down on the enemy; and ordered the Chesterfield to lay by the INTREPID, and the DEPTFORD to supply the INTREPID’S place.

I found the enemy edged away constantly;

and as they went three feet to our one, they would never permit our closing with them, but took advantage of destroying our rigging; for though I closed the Rear-Admiral fast, I found that I could not gain close to the enemy, whose van was fairly drove from their line; but their admiral was joining them, by bearing away.

By this time it was past six, and the enemy’s van and ours were at too great a distance to engage, I perceived some of their ships stretching to the northward; and I imagined they were going to form a new line.

I made the signal for the headmost ships to tack, and those that led before with the larboard tacks to lead with the starboard, that I might, by the first, keep (if possible) the wind of the enemy, and, by the second, between the Rear-Admiral’s division and the enemy, as he had suffered most; as also to cover the INTREPID, which I perceived to be in very bad condition, and whose loss would give the balance very greatly against us, if they attacked us next morning as I expected.

I brought to about eight that night to join the INTREPID, and to refit our ships as fast as possible, and continued doing so all night. The next morning we saw nothing of the enemy, though we were still lying to. Mahon was N.N.W about ten or eleven leagues. I sent cruisers to look out for the INTREPID and CHESTERFIELD, who joined me next day. And having, from a state and condition of the squadron brought me in, found, that the CAPTAIN, INTREPID, and DEFIANCE (which latter has lost her captain), were much damaged in their masts, so that they were in danger of not being able to secure their masts properly at sea; and also, that the squadron in general were very sickly, many killed and wounded, and nowhere to put a third of their number if I made an hospital of the forty-gun ship, which was not easy at sea; I thought it proper in this situation to call a council of war, before I went again to look for the enemy. I desired the attendance of General Stuart, Lord Effingham, and Lord Robert Bertie, and Colonel Cornwallis, that I might collect their opinions upon the present situation of Minorca and Gibraltar, and make sure of protecting the latter, since it was found impracticable either to succour or relieve the former with the force we had. So, though we may justly claim the victory, yet we are much inferior to the weight of their ships, though the numbers are equal; and they have the advantage of sending to Minorca their wounded, and getting reinforcements of seamen from their transports, and soldiers from their camp; all which undoubtedly has been done in this time that we have been lying to to refit, and often in sight of Minorca; and their ships have more than once appeared in a line from our mast-heads.

Admiral John Byng, 25 May, 1756.

The battle was notable for the first time the French had targeted rigging. It was an minor tactical victory for the French (in as much as both fleets were still in being, but the British had failed to dislodge the French from the Mediterranean). However, Byng’s next move turned it into a strategic victory for the French.

The next day, the two fleets had lost contact. Admiral Byng called a council of war on his flagship, HMS Ramilles, which the officers of the fleet attended. The council of war resolved:-

Whether an attack on the French fleet gave any prospect of relieving Mahón ?

– Resolved: It did not.

Whether, if there were no French fleet cruising at Minorca, the British fleet could raise the siege ?

– Resolved: It could not.

Whether Gibraltar would not be in danger, should any accident befall Byng’s fleet?

– Resolved: It would be in danger.

Whether an attack by the British fleet in its present state upon that of the French would not endanger Gibraltar, and expose the trade in the Mediterranean to great hazards ?

– Resolved: It would.

Whether it is not rather for His Majesty’s service that the fleet should proceed immediately to Gibraltar ?

– Resolved: It should proceed to Gibraltar.

Byng’s fleet sailed for Gibraltar, leaving Port Mahón to its fate. On 27 June, it fell to the French when General Sir William Blakeney surrendered St Philip’s Castle.

Minorca fell to the French, together with the strategically important port of Mahón.

“What a scene Byng had open to him, and to throw it all away!”

Boscawen, on hearing of Byng’s withdrawal to Gibraltar.

Unbeknownst to the defeated fleet, Sir Edmund Hawke had sailed on 16 June to Gibraltar to take over the fleet from Admiral Byng, carrying the following orders.

Sir Edward Hawkes instructions

By the commissioners for executing the office of Lord high Admiral of Great Britain and Ireland &c.

Instructions for Sir Edward Hawke, Knight of the Bath, Vice Admiral of the White, hereby appointed commander-in-chief of His Majesty’s ships and vessels employ’d in and about the Mediterranean.

Whereas the King’s pleasure has been signified to us that we should give you directions to repair, without loss of time, to the Mediterranean, to supersede Admiral Byng in the command of His Majesty’s ships there; and that we should appoint some proper flag officer to serve under you in the room of Rear Admiral West: You are hereby required and directed forthwith to repair to Portsmouth, and embark on board His Majesty’s ship the Antelope together with Rear Admiral Saunders, whom we have directed to proceed with you and served under your commands and it being intended that Lord Tyrawley, whom the King has appointed Governor of Gibraltar in the room of Lieut. General Fowke, together with the Earl of Panmure (who is going thither in the room of Major-General Stewart, who is ordered to be recalled), shall proceed in the same ship: you are, as soon as those officers are on board, not to lose a moment is time in proceeding to Gibraltar (the captain of the Antelope being directed to follow your orders), and upon your arrival there, you are to deliver the enclosed packets to Admiral Byng and Rear Admiral West, and immediately take upon you the command of all of His Majesty’s ships, which you may find at Gibraltar, and any others that may be the Mediterranean, all their officers and companies being hereby enjoined to a strict obedience to your orders: and hoisting your flag on board such ship as you shall find from time to time find convenient, you are to assign any other, which you shall judge most fitting for Rear Admiral Saunders, and to take him also under your command.

You are to make an immediate and expeditions inquiry into the conduct and behaviour of the Captains of the ships hereby put under your command: and if you find any reason to believe any of them to have been tardy, and not to have acted with due spirit and vigour for the honour and service of the King and nation, You are forthwith to suspend such Captains and appoint others in their stead, in whom you can confide for properly executing their duty.

You are to order the Captain of the Antelope to receive Admiral Byng and Rear Admiral West on board, and return them to Spithead, and if you shall suspend any of the Captains, you are to send them also home in her.

Having done this, if you shall not be well assurance that Fort St. Philips upon the island of Minorca is in possession of the enemy, you are to use the utmost dispatch in repairing thither with your Squadron, and to exert yourself in doing everything that is possible to be done by you for its relief, and to attack, and to use your utmost endeavours to take, sink, burn or otherwise destroy any squadron of the Enemy’s ships, that may be employed to favour and assist in their attack upon that Fort.

If you shall find the enemy having succeeded, and are in the full possession of Minorca, you are however to endeavour by all means to destroy the French fleet in the Mediterranean, and for that purpose to employ the ships under your command in the most effectual manner you shall be able, and constantly to keep sufficient cruisers round the island of Minorca, and take great care that they exert all possible diligence to prevent the Enemy landing any troops, ammunition, stores or provisions upon that Island, and to annoy and distress them as much as possible: And, in general, you would you are to employ the most utmost vigilance and vigour to annoy and distress the Enemy everywhere within the Extent of your Command, and by every method in means in your power to protect Gibraltar from any Hostile attempts, and also Minorca, should the present attack upon it miscarry: And you were likewise to give all possible attention to the security of the trade of the King’s subjects in and about the Mediterranean and the taking of destroying of any privateers belonging to the Enemy.

If any French Ships of War should escape your Squadron, and proceed out of the Mediterranean, you are forthwith to send to England a proportionable part of the ships under your command observing that you are never to keep more ships in the Mediterranean than shall be necessary for the performance of what is before recommended to you: And, that you may be better in able to perform the services expected of you, you are to take care and keep ships and vessels under your command in constant good condition, and to have them cleaned as often as shall be requisite for that purpose: and to do the same (if Minorca should be in the Enemy’s possession) either in some port in the King of Sardinia’s Domininions or at Gibraltar, as shall be most convenient.

And whereas the King’s pleasure is signified to Lord Tyrawley, to cause the troops under his command to be disposed of as he shall see best for His Majesty’s Service, and the preservation of his possessions in the Mediterranean and that his Lordship does from time to time embark such Detachments, Stores, Arms and Ammunition, and provision for the relief of Minorca, as the commanding sea officer in the Mediterranean shall undertake to carry thither, and that he gives other assistance to the garrison of St Philip and the island of Minorca as shall be in his power, consistent with the safety of the Garrison of Gibraltar: you are to consult with Lord Tyrawley in relation to the said particulars, and to co-operate with him in everything that may tend to the good of the King’s service and the preservation of the possessions in the Mediterranean: And Lord Tyrawley being directed to establish an Hospital at Gibraltar, for the relief of sick and wounded men that may be sent thither from time to time from Minorca: you are to call such men to be transported from that Island to Gibraltar as often as possible.

And Whereas a number of transport will shortly depart from Plymouth, with two Battalions on board for Gibraltar and will be convoyed thither by the Jersey and Gosport: if the situation of matters shall be such as to require your detaining them or any of them for transporting forces from Gibraltar to Minorca, you are at liberty to keep them as may be wanting, taking care to dismiss and send them to England as soon as the service would admit of so doing, either under convoy of the Antelope, or if she shall be departed, of the first shall sell afterwards.

In cases your disability, by sickness or otherwise, you are to leave these instructions, or any others which you shall receive from us, with Rear Admiral Saunders, who is hereby required to put the same in execution: And if this case should happen, every commander of His Majesty’s ships and vessels at Gibraltar, and in the Mediterranean, is hereby required and directed to put himself under the command of Rear Admiral Saunders, and follow his orders given, &c, the 8th June 1756

ANSON W ROWLEY. BATEMAN.

Rd EDGCUMBE

By &c. J. CLEVELAND.

It seems inconceivable that had Admiral Byng had these orders, he would have give up the chase against the French fleet and return to Gibraltar. But sail to Gibraltar he did, to be relieved of his command by Sir Edmund Hawke, and thence to be returned forthwith to England.

Byng’s Plea

With thirteen ships to twelve says Byng

It were a shame to meet ’em

And then with twelve to twelve a thing

Impossible to beat ’em

When more to many less to few

And even still not right

Arithmatic will plainly shew

T’were wrong in Byng to fight.

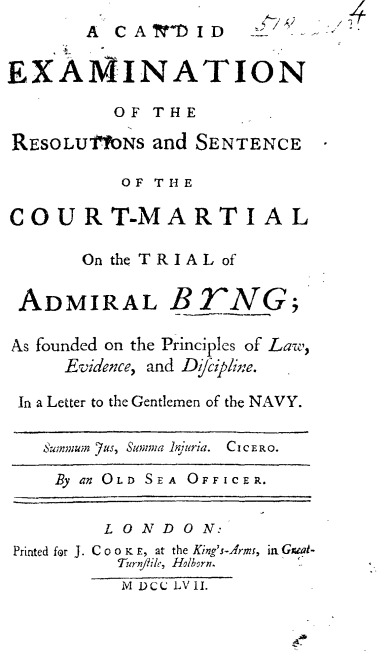

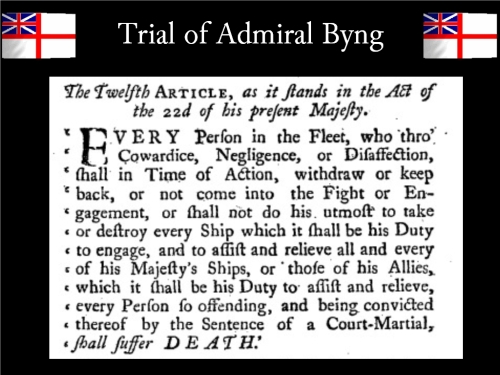

The trial of Admiral Byng forms an important footnote to the Battle of Minorca.

News of the fleet action off Minorca reached Britain from de la Galissonniere’s published account on 2 June. Galissoniere reported that on 19 May the English “seemed unwilling to engage” and that on 20 May, “the English had the advantage of the wind, but still seemed unwilling to fight”; he expected to be attacked on 21 May, but “the English had disappeared”. This, and the loss of Minorca divided British public opinion on Byng’s conduct. His own account reached the Admiralty on 23 June, and a much edited version appeared in the London Chronicle on 26 June.

Byng returned to England in July 1756, where he was promptly arrested, pending a court martial. His trial began on board the St. George in Portsmouth Harbour on December 27th, and continued until January 27th, 1757.

Public opinion divided ahead of the trial.

“To the block with Newcastle and the yard arm for Byng”

Alternatively, as a riposte to “Sing Tantararara, Hang Byng” a supportive popular ballard was sung by the London ballard singers.

The furore resulted in the fall of the Government in December 1756, to be replaced by a new one led by William Pitt, with the Duke of Devonshire as Prime Minister.

The trial of Admiral Byng began on board the St. George in Portsmouth Harbour on December 27th

and continued until January 27th, 1757. Crucial to the outcome would be the opinion of his brother officers in the Royal Navy. The public utterings were against him.

“No doubt but Mr Byng’s behaviour on the late occasion off Mahon must surprise and anger you and every right thinking man in the kingdom”

Captain S Faulknor

“Sad indeed: He’s brought more disgrace on the British flag than ever his father the great Lord Torrington did honour to it”.

Admiral Boscawen

The court-martial, summoned to try Byng, consisted of Vice Admiral Thomas Smith, who was president, Rear-Admirals Francis Holburne, Harry Norris and Thomas Broderick, and nine captains. After hearing the evidence, the court agreed to a number of resolutions or conclusions, including:

That when the British fleet, on the starboard tack, was stretched abreast, or was about abeam, of the enemy’s line, Admiral Byng should have caused his ships to tack together, and should have immediately borne right down on the enemy; his van steering for the enemy’s van, his rear for its rear, each ship making for the one opposite to her in the enemy’s line, under such sail as would have enabled the worst sailer to preserve her station in the line of battle.

That the Admiral retarded the rear division of the British fleet from closing with and engaging the enemy, by shortening sail, in order that the Trident and Princess Louisa might regain their stations ahead of the Ramalies; whereas he should have made signals to those ships to make more sail, and should have made so much sail himself as would enable the Culloden, the worst sailing ship in the Admiral’s division, to keep her station with all her plain sails set, in order to get down to the enemy with as much expedition as possible, and thereby properly support the division of Rear-Admiral West.

That the Admiral did wrong in ordering the fire of the Ramillies to be continued before he had placed her at proper distance from the enemy, inasmuch as he thereby not only threw away his shot, but also occasioned a smoke, which prevented his seeing the motions of the enemy and the positions of the ships immediately ahead of the Ramillies.

That after the ships which had received damage in the action had been refitted as circumstances would permit, the Admiral ought to have returned with his squadron off Port Mahon, and endeavoured to open communication with the castle, and to have used every means in his power for its relief, before returning to Gibraltar.

Thus Admiral Byng stood accused of violating article 12 of the Articles of War of the Royal Navy.

At the trial, the testimony of two witnesses bore heavily against Admiral Byng; that of General Sir William Blakeney, commander of St Philip’s Castle on Minorca, and Captain Everett of the Buckingham, the flagship of Rear Admiral West. General Blakeney suggested that Byng could have landed troops at Port Mahon to help him defend St Philip’s Castle. Captain Everett suggested that Byng’s division in the Battle of Minorca has insufficent sail to close down upon the French, and thus lost the battle.

Byng conducted his own defence, and gave a spirited response.

Now instead of my retreating from an inferior Force, that a superior Force retreated from me, when the Fleet was unable to pursue, I shall manifest beyond all contradiction, and cannot help observing, that perhaps I am the first Instance of a Commander in Chief, whose disgrace proceeded from so unfortunate a mistake.

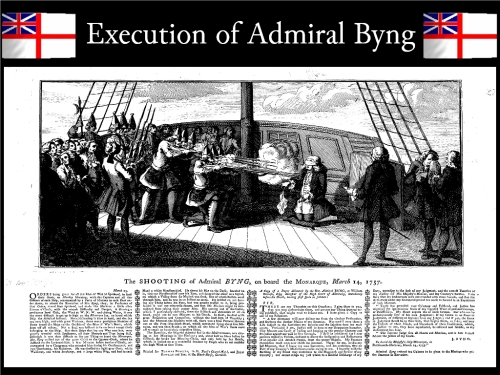

The court found that Byng had failed in his duty to relieve Minorca, specifically St. Philip’s Castle, and that he had failed to destroy the French squadron in battle. They sentenced him to death on 27 January 1757 for failing to abide by the Articles of War according to Article 12.

The change in government had brought supporters of Byng to power, and he had hope that the conviction would be overturned, despite the fury of the public, and the hostility of his Naval colleagues. Unfortunately, a letter from Voltaire to Byng was found and suggested treason.

An appeal for clemency to King George II was rejected, and Admiral John Byng died by firing squad at noon on the quarterdeck of Monarch on 14 March 1757.

![]() Public outrage at the execution of Admiral Byng

Public outrage at the execution of Admiral Byng

led to the fall of the government.

The two great opponents, the Duke of Newcastle and William Pitt joined together to make a new government, lasting until 1763, with Pitt leading matters relating to defence and foreign policy, and The Duke of Newcastle leading the Commons, finance and patronage.

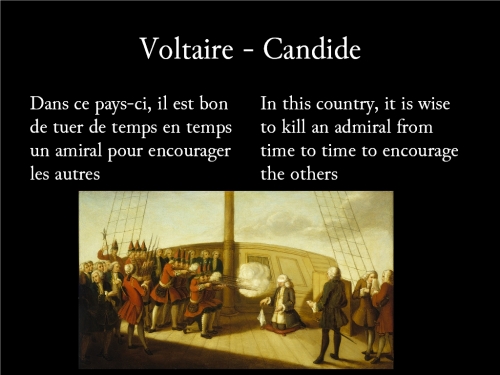

Voltaire commented in his novel Candide an ironic witticism on the fate of Admiral Byng.

with the phrase “pour encourager les autres” entering into English sayings.

Dr Johnson, in Boswell’s Life of Johnson commented that “the nation has long been satisfied that his life was sacrificed to the political fervour of the times”, and reports the epitaph for Admiral Byng in the Torrington family vault in All Saint’s Church, Southill, Bedfordshire.